Diagnosis and management of endometriosis: summary of NICE guidance

BMJ 2017; 358 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j3935 (Published 06 September 2017) Cite this as: BMJ 2017;358:j3935

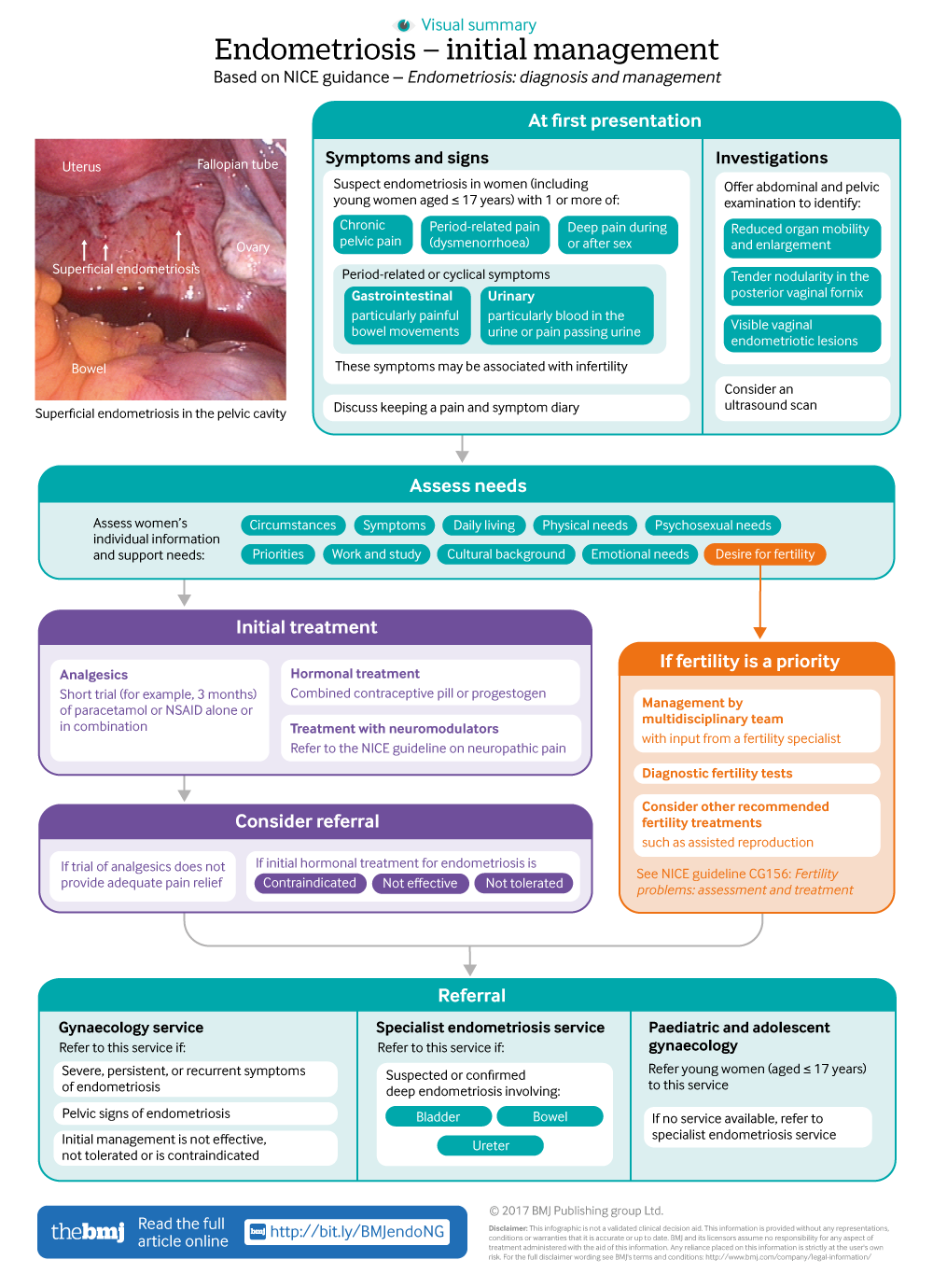

Infographic available

Click here for a visual summary of newly updated NICE guidance for endometriosis diagnosis and management.

- Laura Kuznetsov, systematic reviewer1,

- Katharina Dworzynski, guideline lead1,

- Melanie Davies, clinical advisor and consultant gynaecologist1 2,

- Caroline Overton, chair of Guideline Committee and consultant gynaecologist, subspecialist in reproductive medicine and laparoscopic surgery3

- on behalf of the Guideline Committee

- 1National Guideline Alliance, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, London NW1 4RG, UK

- 2University College London Hospitals, London, UK

- 3St Michael’s University Hospital, Bristol, UK

- Correspondence to: M Davies mdavies{at}rcog.org.uk

What you need to know

Endometriosis can be difficult to diagnose, with some studies showing a delay in diagnosis of 4-10 years, resulting in decreased quality of life and disease progression

Endometriosis cannot be ruled out by a normal examination and pelvic ultrasound

Hormonal treatments for endometriosis suppress menstruation and reduce pain. They are contraceptive but have no effect on subsequent fertility after discontinuation

Refer women to a gynaecology service if they have severe, persistent, or recurrent symptoms of endometriosis, if they have pelvic signs of endometriosis, or if initial management is not effective, not tolerated, or is contraindicated

Endometriosis can be a long term condition, with substantial physical, sexual, psychological, and social impact

Endometriosis is one of the most common gynaecological disorders, affecting an estimated 10% of women in the reproductive age group (usually 15-49 years old), and in the UK it is the second most common gynaecological condition (after fibroids).1 Endometriosis is hormone mediated and is associated with menstruation. The precise cause is not known, but it is widely accepted that endometrial cells deposited in the pelvis by retrograde menstruation are capable of implantation and development. It is a long term condition causing pelvic pain, painful periods, and subfertility. Endometriosis presents a diagnostic and clinical challenge, with many women left undiagnosed, often for many years. Small observational studies have reported delays of 4-10 years in diagnosis,23 which can result in decreased quality of life4 and disease progression.5 The diagnostic delay is not limited to adults; endometriosis is also often missed in adolescent girls,6 and this guideline aims to improve care by highlighting this age group in some recommendations.

This article summarises the most recent recommendations from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) on diagnosis and management of endometriosis.7 The recommendations were based on consideration of the available evidence, which was mostly of very low quality and seldom of moderate or high quality, and the expert opinion of the Guideline Committee (GC).

The overall aim of the guideline is to improve the diagnosis and management of endometriosis in community services, gynaecology services, and specialist endometriosis services (endometriosis centres). It includes women with confirmed or suspected endometriosis, including recurrent endometriosis, and women who do not have symptoms but have endometriosis discovered incidentally. The guideline also addresses the care of adolescent girls. This summary focuses on investigation, early management, and referral for women with suspected endometriosis, and is aimed mainly at general practitioners and healthcare professionals in community services where women will first present.

Recommendations

NICE recommendations are based on systematic reviews of the best available evidence and explicit consideration of cost effectiveness. When minimal evidence is available, recommendations can be based on the Guideline Committee’s (GC) experience and opinion of what constitutes good practice. Evidence levels for the recommendations are given in italic in square brackets.

When to suspect endometriosis

Recommendations on endometriosis symptoms and signs are summarised in box 1, and a pathway for initial management of suspected endometriosis is presented in the infographic (the full NICE pathway for diagnosis and management of suspected endometriosis is available in appendix 1 on bmj.com).

Endometriosis symptoms and signs

Suspect endometriosis in women (including young women aged ≤17 years) presenting with one or more of:

Chronic pelvic pain

Period related pain (dysmenorrhoea) affecting daily activities and quality of life

Deep pain during or after sexual intercourse

Period related or cyclical gastrointestinal symptoms, in particular painful bowel movements

Period related or cyclical urinary symptoms, in particular blood in the urine or pain passing urine

Infertility in association with one or more of the above.

[Based on moderate quality evidence from quantitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

Inform women with suspected or confirmed endometriosis that keeping a pain and symptom diary can aid discussions. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Offer an abdominal and pelvic examination to women with suspected endometriosis to identify abdominal masses and pelvic signs, such as reduced organ mobility and enlargement, tender nodularity in the posterior vaginal fornix, and visible vaginal endometriotic lesions. [Based on moderate quality evidence from quantitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

Investigating suspected endometriosis

Do not exclude the possibility of endometriosis if the abdominal or pelvic examination, ultrasound scan, or magnetic resonance imaging is normal. If clinical suspicion remains or symptoms persist, consider referral for further assessment and investigation (see below). [Based on low to very low quality evidence from quantitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

Imaging: ultrasound scanning

Consider transvaginal ultrasound:

To investigate suspected endometriosis even if the pelvic and abdominal examination is normal

To identify endometriomas and deep endometriosis involving the bowel, bladder, or ureter.

[Based on low to very low quality evidence from quantitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

If a transvaginal scan is not appropriate (for example, in women who have never had sexual intercourse), consider a transabdominal ultrasound scan of the pelvis. [Based on low to very low quality evidence from quantitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

Imaging: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Do not use pelvic MRI as the primary investigation to diagnose endometriosis in women with symptoms or signs suggestive of endometriosis. [Based on very low quality evidence from quantitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

Consider pelvic MRI to assess the extent of deep endometriosis involving the bowel, bladder, or ureter. [Based on very low quality evidence from quantitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

Ensure that MRI scans are interpreted by a healthcare professional with specialist expertise in gynaecological imaging. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Blood tests: cancer antigen 125 (CA-125)

Do not use serum CA-125 to diagnose endometriosis. [Based on very low quality evidence from quantitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

If a coincidentally reported serum CA-125 level is available, be aware that:

A raised serum CA-125 titre (≥35 IU/mL) may be consistent with having endometriosis

Endometriosis may be present despite a normal serum CA-125 level (<35 IU/mL).

[Based on very low quality evidence from quantitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

Diagnostic laparoscopy

Consider laparoscopy to diagnose endometriosis in women with suspected endometriosis, even if the ultrasound scan was normal. [Based on moderate to very low quality evidence from quantitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

During a diagnostic laparoscopy, a gynaecologist with training and skills in laparoscopic surgery should perform a systematic inspection of the pelvis. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Initial management of suspected endometriosis

If endometriosis is suspected after a thorough history and examination and if an initial trial with paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), or both, and management with hormonal treatment are ineffective or not tolerated, it is recommended that primary health care doctors could consider a referral to a gynaecology, paediatric and adolescent gynaecology, or specialist endometriosis service. In women for whom fertility is a priority, consider managing endometriosis related subfertility in a multidisciplinary team with input from a fertility specialist.

Analgesics

For women with endometriosis related pain, health professionals should discuss the benefits and risk of analgesics, taking into account any comorbidities and the woman’s preferences. Consider a short trial (for example, 3 months) of paracetamol or NSAID, alone or in combination, for first line management of endometriosis related pain. If this does not provide adequate pain relief, consider other forms of pain management and referral for further assessment. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Hormonal treatments

Explain to women with suspected or confirmed endometriosis that hormonal treatment for endometriosis can reduce pain and has no permanent negative effect on subsequent fertility. [Based on high to low quality evidence from quantitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

Offer hormonal treatment (such as combined oral contraceptive or a progestogen) to women with suspected, confirmed, or recurrent endometriosis. [Based on high to low quality evidence from quantitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

Not all combined oral contraceptives and progestogens have UK authorisation for this indication. Prescribers should follow relevant professional guidance for prescribing unlicensed medicines.

Do not offer hormonal treatment to women with endometriosis who are trying to conceive, because it does not improve spontaneous pregnancy rates. [Based on high to low quality evidence from quantitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

If initial hormonal treatment for endometriosis is not effective, not tolerated, or is contraindicated, refer the woman to a gynaecology service (see box 2), specialist endometriosis service (endometriosis centres, box 2), or paediatric and adolescent gynaecology service for investigation and treatment options. [Based on high to low quality evidence from quantitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

Organisation of care of women with suspected or confirmed endometriosis

Community, gynaecology, and specialist endometriosis services (endometriosis centres) should:

Provide coordinated care for women with suspected or confirmed endometriosis

Have processes in place for prompt diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis, because delays can affect quality of life and result in disease progression

Gynaecology services for women with suspected or confirmed endometriosis should have access to:

A gynaecologist with expertise in diagnosing and managing endometriosis, including training and skills in laparoscopic surgery

A gynaecology specialist nurse with expertise in endometriosis

A multidisciplinary pain management service

A healthcare professional with an interest in gynaecological imaging

Fertility services

Specialist endometriosis services (endometriosis centres) should have access to:

Gynaecologists with expertise in diagnosing and managing endometriosis, including advanced laparoscopic surgical skills

A colorectal surgeon with an interest in endometriosis

A urologist with an interest in endometriosis

An endometriosis specialist nurse

A multidisciplinary pain management service with expertise in pelvic pain

A healthcare professional with specialist expertise in gynaecological imaging of endometriosis

Advanced diagnostic facilities (for example, radiology and histopathology)

Fertility services

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

When to refer women with suspected or confirmed endometriosis?

Consider referring women to a gynaecology service for an ultrasound or gynaecology opinion if:

They have severe, persistent, or recurrent symptoms of endometriosis

They have pelvic signs of endometriosis

Initial management is not effective, not tolerated, or is contraindicated.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Refer women to a specialist endometriosis service (endometriosis centre) if they have suspected or confirmed deep endometriosis involving the bowel, bladder, or ureter. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Evidence suggests endometriosis is often not suspected in young women6 and, because of this they are often not referred to the right services for endometriosis.

Consider referring young women (aged ≤17 years) with suspected or confirmed endometriosis to a paediatric and adolescent gynaecology service, gynaecology service, or specialist endometriosis service (endometriosis centre) depending on local service provision. [Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

What are the surgical options?

Discuss surgical management options with women with suspected or confirmed endometriosis. In most cases surgical management would be considered after conservative treatments have been unsuccessful unless the woman shows signs of deep endometriosis involving the bowel, bladder, or ureter.

Discussions may include:

What a laparoscopy involves

That laparoscopy may include surgical treatment (with prior patient consent)

How laparoscopic surgery could affect endometriosis symptoms

The possible benefits, risks, and complications of laparoscopic surgery

The possible need for further surgery (for example, for recurrent endometriosis or if complications arise)

The possible need for further planned surgery for deep endometriosis involving the bowel, bladder, or ureter.

[Based on the experience and opinion of the GC]

Surgical management if fertility is a priority

The management of endometriosis related subfertility should have multidisciplinary team involvement with input from a fertility specialist. This should include the recommended diagnostic fertility tests or preoperative tests, as well as other recommended fertility treatments such as assisted reproduction that are included in the NICE guideline on fertility problems (www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg156).

What information and support is available?

The Guideline Committee acknowledged that for most women the healthcare professional is the first point of contact regarding information about their condition, and the GC highlighted that the information provided is often inadequate.8 It is important for women to understand the consequences of their choices (for example, choosing hormone treatment that is contraceptive) and be able to make an informed decision. However, the challenge for healthcare professionals is to tailor information to individual needs, preferences, and circumstances while also allowing for flexibility, because information needs may change with time, if new symptoms develop, or if priorities change.

The GC made the following recommendations:

Be aware that endometriosis can be a long term condition, and can have a significant physical, sexual, psychological, and social impact. [Based on moderate to low quality evidence from qualitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

Assess the individual information and support needs of women with suspected or confirmed endometriosis, taking into account their circumstances, symptoms, priorities, desire for fertility, aspects of daily living, work and study, cultural background, and their physical, psychosexual, and emotional needs. [Based on moderate to low quality evidence from qualitative studies and the experience and opinion of the GC]

Organisation of care

Recommendations on organisation of care are summarised in box 2.

Implementation

There are challenges to delivering high quality care to women with endometriosis. Women typically present to community services including general practitioners, practice nurses, school nurses, and sexual health services, and the information in this guideline will help diagnosis and guide referral. There are currently geographical inequalities in access to specialist care. The recommendations related to organisation of care will improve access to gynaecology specialist nurses with expertise in endometriosis. Implementation related to surgery in gynaecological and specialist endometriosis services can also be improved by providing clearer guidance on consent for diagnostic laparoscopy, since it often serves a dual purpose of diagnosis as well as management. New guidance on this from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists could facilitate this process.9

To help women make choices in the management of their condition, a patient decision aid for hormonal treatment is in development and will be published alongside the guideline.

Guidelines into practice

How might you use the information in this article to help achieve prompt investigation and diagnosis for women presenting with symptoms suggestive of endometriosis?

Are you aware of how to refer to specialist services locally if you need support managing or diagnosing a patient with endometriosis?

What will you do differently as a result of reading this article?

Future research

The GC prioritised the following research recommendations:

What information and support interventions are effective to help women with endometriosis deal with their symptoms and improve their quality of life?

Are specialist lifestyle interventions (diet and exercise) effective for women with endometriosis?

Are pain management programmes a clinically and cost effective intervention for women with endometriosis?

Is laparoscopic treatment (excision or ablation) of peritoneal disease in isolation effective for managing endometriosis related pain?

How patients were involved in the creation of this article

Committee members involved in this guideline included two lay members with direct experience of endometriosis and one lay member from an organisation that represents women with endometriosis, who all contributed to the formulation of the recommendations summarised here.

Methods

This guidance was developed by the National Guideline Alliance in accordance with NICE guideline development methods (www.nice.org.uk/media/default/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/developing-nice-guidelines-the-manual.pdf). A Guideline Committee (GC) was established by the National Guideline Alliance, chaired by a consultant gynaecologist, which comprised healthcare professionals (one general practitioner, one consultant in pain medicine, one consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist, one professor of gynaecology and reproductive science, two endometriosis clinical nurse specialists, and two consultant gynaecologists specialising in endometriosis), one clinical commissioner, and three lay members.

The GC co-opted one consultant radiologist, one associate professor of gynaecology and reproductive medicine with a particular interest in adolescent care, one consultant urological surgeon, one consultant gynaecological pathologist, one clinical psychologist with a particular interest in pelvic pain, and one consultant colorectal surgeon.

The GC identified relevant clinical questions, collected and appraised clinical evidence, and evaluated the cost effectiveness of proposed interventions where possible. Quality ratings of the evidence were based on GRADE methodology (www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). These relate to the quality of the available evidence for assessed outcomes rather than the quality of the study. The scope and the draft of the guideline went through a rigorous reviewing process, in which stakeholder organisations were invited to comment; the group took all comments into consideration when producing the final guideline. Two different versions of this guideline have been produced: a full version containing all the evidence, the process undertaken to develop the recommendations, and all the recommendations, known as the “full guideline”; and a short version containing a list of all the recommendations, known as the “short guideline.” Both versions are available from the NICE website (www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng37).

A formal review of the need to update a guideline is usually undertaken by NICE three years after its publication. NICE will conduct a review to determine whether the evidence base has progressed significantly to alter the guideline recommendations and warrants an update.

Acknowledgments

The members of the Guideline Committee were (shown alphabetically): Rachel Brown, Dominic Byrne, Natasha Curran, Alfred Cutner, Cathy Dean, Lynda Harrison, Jed Hawe, Lyndsey Hogg, Andrew Horne, Jane Hudson-Jones, Wendy-Rae Mitchel, Caroline Overton (chair), and Carol Pearson. Co-opted members: Moji Balogun, Christian Becker, Mohammed Belal, Natalie Lane, Sanjiv Manek, and Tim Rockall.

The members of the National Guideline Alliance technical team were (shown alphabetically): Alexander Bates, Zosia Beckles, Shona Burman-Roy, Anne Carty, Melanie Davies, Katharina Dworzynski, Annabel Flint, Maryam Gholitabar, Elise Hasler, Sadia Janjua, Laura Kuznetsov, Sabrina Naqvi, Amir Omidvari, Hugo Pedder, and Ferruccio Pelone.

Footnotes

Contributors All authors contributed to the initial draft of this article, helped revise the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Funding The National Guideline Alliance was commissioned and funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence to develop this guideline and write this BMJ summary.

Competing interests: We declare the following interests based on NICE's policy on conflicts of interests (available at http://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/Who-we-are/Policies-and-procedures/code-of-practice-for-declaring-and-managing-conflicts-of-interest.pdf): MD and CO have private practice that may include treating women with endometriosis. These authors’ full statements can be viewed at www.bmj.com/content/bmj/358/bmj.j3935/related#datasupp.