Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To investigate the association between body mass index (BMI) and functional health according to age and the support available from a close confidant.

DESIGN: A cross-sectional population-based study.

PARTICIPANTS: A total of 20 921 participants in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition, aged 41–80 y resident in Norfolk, England.

MEASUREMENTS: Standardised clinic-based assessment of BMI, self-reported functional health status assessment (according to the anglicised Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Survey questionnaire) and the availability (and quality) of a close confiding relationship.

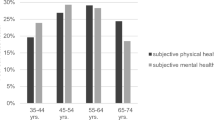

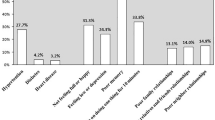

RESULTS: Self-reported physical functioning declined steadily with increasing age. Obesity (BMI ≥30) was strongly associated with self-reported physical functional health, equivalent to being 11 y older for men and 16 y older for women (after adjustment that included prevalent chronic physical conditions and cigarette smoking). This adverse effect of obesity on physical functional health was found to increase with age for both men and women. Perceived inadequacy of a confiding relationship was associated with reduced physical functional capacity, equivalent to being 4 y older for men and 5 y older for women. For those with markedly inadequate confidant relationships, the impact of obesity on physical functional capacity was approximately constant by age. For those not critical of the adequacy of their confiding relationships, the impact of obesity was least for those younger but rose to equivalent levels as those with markedly inadequate confidant relationships among older participants.

CONCLUSIONS: The availability of a close confidant relationship (perceived as uncritical and characterised by the absence of shared negative interactions) may delay the impact of obesity in reducing physical functional capacity.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lee IM, Manson JE, Hennekens CH, Paffenbarger RS . Body-weight and mortality—a 27-year follow-up of middle-aged men. JAMA 1993; 270: 2823–2828.

Manson JE, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Hankinson SE, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE . Body-weight and mortality among women. N Engl J Med 1995; 333: 677–685.

Ferraro KF, Su YP, Gretebeck RJ, Black DR, Badylak SF . Body mass index and disability in adulthood: a 20-year panel study. Am J Public Health 2002; 92: 834–840.

Popkin BM . The shift in stages of the nutritional transition in the developing world differs from past experiences! Public Health Nutr 2002; 5 (Special Issue 1A): 205–214.

World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: Report of a WHO Consultation on Obesity (WHO/NUT/NCD Technical Report Series 894). World Health Organization: Geneva; 2000.

World Health Organization. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. Report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation (WHO Technical Report Series 916). World Health Organization: Geneva; 2003.

National Audit Office. Tackling obesity in England. The Stationery Office: London; 2001.

Stunkard AJ, Wadden TA . Psychological aspects of severe obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 1992; 55: S524–S532.

Gortmaker SL, Must A, Perrin JM, Sobol AM, Dietz WH . Social and economic consequences of overweight in adolescence and young adulthood. N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 1008–1012.

Roberts RE, Kaplan GA, Shema SJ, Strawbridge WJ . Are the obese at greater risk for depression? Am J Epidemiol 2000; 152: 163–170.

Puhl R, Brownell KD . Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obes Res 2001; 9: 788–805.

Stunkard AJ, Faith MS, Allison KC . Depression and obesity. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54: 330–337.

Han TS, Tijhuis MAR, Lean MEJ, Seidell JC . Quality of life in relation to overweight and body fat distribution. Am J Public Health 1998; 88: 1814–1820.

Brown WJ, Dobson AJ, Mishra G . What is a healthy weight for middle aged women? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1998; 22: 520–528.

Doll HA, Petersen SEK, Stewart-Brown SL . Obesity and physical and emotional well-being: associations between body mass index, chronic illness, and the physical and mental components of the SF-36 questionnaire. Obes Res 2000; 8: 160–170.

Larsson U, Karlsson J, Sullivan M . Impact of overweight and obesity on health-related quality of life—a Swedish population study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002; 26: 417–424.

Rowe JW, Kahn RL . Successful aging. Gerontologist 1997; 37: 433–440.

Seeman TE, McEwen BS, Rowe JW, Singer BH . Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98: 4770–4775.

Vaillant GE, Mukamal K . Successful aging. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158: 839–847.

Ferraro KF, Booth TL . Age, body mass index, and functional illness. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1999; 54: S339–S348.

Kaplan GA, Salonen JT, Cohen RD, Brand RJ, Syme SL, Puska P . Social connections and mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular disease: prospective evidence from Eastern Finland. Am J Epidemiol 1988; 128: 370–380.

Vogt TM, Mullooly JP, Ernst D, Pope CR, Hollis JF . Social networks as predictors of ischemic heart disease, cancer, stroke, and hypertension—incidence, survival and mortality. J Clin Epidemiol 1992; 45: 659–666.

Eng PM, Rimm EB, Fitzmaurice G, Kawachi I . Social ties and change in social ties in relation to subsequent total and cause-specific mortality and coronary heart disease incidence in men. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 155: 700–709.

Michael YL, Colditz GA, Coakley E, Kawachi I . Health behaviors, social networks, and healthy aging: cross-sectional evidence from the Nurses' Health Study. Qual Life Res 1999; 8: 711–722.

Michael YL, Berkman LF, Colditz GA, Kawachi I . Living arrangements, social integration, and change in functional health status. Am J Epidemiol 2001; 153: 123–131.

Seeman TE . Social ties and health: the benefits of social integration. Ann Epidemiol 1996; 6: 442–451.

Berkman LF, Glass T . Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I (eds). Social epidemiology. Oxford University Press: New York; 2000. pp 137–173.

Seeman TE . Health promoting effects of friends and family on health outcomes in older adults. Am J Health Promot 2000; 14: 362–370.

Kawachi I, Berkman LF . Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health 2001; 78: 458–467.

Day N, Oakes S, Luben R, Khaw KT, Bingham S, Welch A, Wareham N . EPIC-Norfolk: study design and characteristics of the cohort. Br J Cancer 1999; 80 (Suppl 1): 95–103.

Surtees PG, Wainwright NWJ, Brayne C . Psychosocial aetiology of chronic disease: a pragmatic approach to the assessment of lifetime affective morbidity in an EPIC component study. J Epidemiol Commun Health 2000; 54: 114–122.

Elias P, Halstead K, Prandy K . CASOC: Computer-Assisted Standard Occupational Coding. HMSO: London; 1993.

Meltzer H, Gill B, Petticrew M, Hinds K . OPCS surveys of psychiatric morbidity in Great Britain. Report 1. The prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households. HMSO: London; 1995.

Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NMB, Ocathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, Westlake L . Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire—new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ 1992; 305: 160–164.

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD . The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30: 473–483.

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B . SF-36 Health Survey: manual and interpretation guide. Nimrod Press: Boston; 1993.

Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, Wells K, Rogers WH, Berry SD, McGlynn EA, Ware JE . Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions—results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 1989; 262: 907–913.

McDowell I, Newell C . Measuring health. A guide to rating scales and questionnaires, 2nd edn Oxford University Press: New York; 1996.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller S . SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a user's manual. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center: Boston; 1994.

Jenkinson C . Comparison of UK and US methods for weighting and scoring the SF-36 summary measures. J Public Health Med 1999; 21: 372–376.

Stansfeld S, Marmot M . Deriving a survey measure of social support: the reliability and validity of the Close Persons Questionnaire. Soc Sci Med 1992; 35: 1027–1035.

Stansfeld SA, Bosma H, Hemingway H, Marmot MG . Psychosocial work characteristics and social support as predictors of SF-36 health functioning: The Whitehall II study. Psychosom Med 1998; 60: 247–255.

Surtees PG, Wainwright NWJ, Khaw KT, Luben RL, Brayne C, Day N . Inflammatory dispositions: a population-based study of the association between hostility and peripheral leukocyte counts. Pers Indiv Differ 2003; 35: 1271–1284.

Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Wright L . Short Form-36 (SF-36) health survey questionnaire—normative data for adults of working age. BMJ 1993; 306: 1437–1440.

Bowling A, Bond M, Jenkinson C, Lamping DL . Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Survey questionnaire: which normative data should be used? Comparisons between the norms provided by the Omnibus survey in Britain, the Health Survey for England and the Oxford Healthy Life Survey. J Public Health Med 1999; 21: 255–270.

Prescott-Clarke P, Primatesta P (eds). Health survey for England 1996: a survey carried out on behalf of the Department of Health. The Stationery Office: London; 1998.

Kuskowska-Wolk A, Bergstrom R, Bostrom G . Relationship between questionnaire data and medical records of height, weight and body mass index. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1992; 16: 1–9.

Plankey MW, Stevens J, Flegal KM, Rust PF . Prediction equations do not eliminate systematic error in self-reported body mass index. Obes Res 1997; 5: 308–314.

Niedhammer I, Bugel I, Bonenfant S, Goldberg M, Leclerc A . Validity of self-reported weight and height in the French GAZEL cohort. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000; 24: 1111–1118.

Sargeant LA, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT . Family history of diabetes identifies a group at increased risk for the metabolic consequences of obesity and physical inactivity in EPIC-Norfolk: a population based study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000; 24: 1333–1339.

Taft C, Karlsson J, Sullivan M . Do SF-36 summary component scores accurately summarize subscale scores? Qual Life Res 2001; 10: 395–404.

Taft C, Karlsson J, Sullivan M . Interpreting SF-36 summary health measures: a response—reply. Qual Life Res 2001; 10: 415–420.

Fontaine KR, Redden DT, Wang CX, Westfall AO, Allison DB . Years of life lost due to obesity. JAMA 2003; 289: 187–193.

Broman CL . Social relationships and health-related behavior. J Behav Med 1993; 16: 335–350.

Ford ES, Ahluwalia IB, Galuska DA . Social relationships and cardiovascular disease risk factors: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Prev Med 2000; 30: 83–92.

Unger JB, McAvay G, Bruce ML, Berkman L, Seeman T . Variation in the impact of social network characteristics on physical functioning in elderly persons: MacArthur studies of successful aging. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1999; 54: S245–S251.

Zunzunegui MV, Alvarado BE, Del Ser T, Otero A . Social networks, social integration, and social engagement determine cognitive decline in community-dwelling Spanish older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2003; 58: S93–S100.

Wing RR, Jeffery RW . Benefits of recruiting participants with friends and increasing social support for weight loss and maintenance. J Consult Clin Psychol 1999; 67: 132–138.

Fairburn CG, Brownell KD (eds) Eating disorders and obesity: a comprehensive handbook, 2nd edn. The Guildford Press: London; 2002.

Hogan BE, Linden W, Najarian B . Social support—do the interventions work? Clin Psychol Rev 2002; 22: 381–440.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and general practitioners who took part in this study and staff associated with the research programme. EPIC-Norfolk is supported by programme grants from the Cancer Research Campaign and Medical Research Council with additional support from the Stroke Association, the British Heart Foundation, the Department of Health, the Food Standards Agency and the Wellcome Trust, and the Europe Against Cancer Programme of the Commission of the European Communities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

In the CPQ,41 three types of support were described: confiding/emotional support (seven items), practical support (three items) and negative aspects of the relationship with the closest person (four items). CPQ items included in the HLEQ are shown below according to support category type. Two original confiding/emotional support CPQ items were combined to form question (c) below in the HLEQ. This section of the HLEQ was introduced with the question:

Question: Of your spouse/partner, relatives, friends and acquaintances, is there someone you have felt the closest to during the past 12 months; someone from who you can obtain support, either emotional or practical?

Response: yes/no

Confiding/emotional support items (4):

(a) How much in the last 12 months did this person make you feel good about yourself?

(b) How much in the last 12 months did you share interests, hobbies and fun with this person?

(c) How much in the last 12 months did you confide in this person, so much that you trusted them with your most personal worries and problems?

(d) How much in the last 12 months did he/she talk about his/her personal worries with you?

Items concerned with negative aspects of the relationship (4):

(e) How much in the last 12 months did this person give you worries, problems and stress?

(f) How much in the last 12 months would you have liked to have confided more in this person?

(g) How much in the last 12 months did talking to this person make things worse?

(h) How much in the last 12 months would you have liked more practical help with major things from this person?

Items concerned with practical support (2):

(i) How much in the last 12 months did you need practical help from this person with major things (eg look after you when ill, help with money, children)?

(j) How much in the last 12 months did this person give you practical help with major things?

Response: a great deal/quite a lot/a little/not at all.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Surtees, P., Wainwright, N. & Khaw, KT. Obesity, confidant support and functional health: cross-sectional evidence from the EPIC-Norfolk cohort. Int J Obes 28, 748–758 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802636

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802636

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Self-reported physical functional health predicts future bone mineral density in EPIC-Norfolk cohort

Archives of Osteoporosis (2022)

-

Association of self-rated health with multimorbidity, chronic disease and psychosocial factors in a large middle-aged and older cohort from general practice: a cross-sectional study

BMC Family Practice (2014)

-

Mental Health and Obesity: A Meta-Analysis

Applied Research in Quality of Life (2014)

-

Social Adversity Experience and Blood Pressure Control Following Antihypertensive Medication Use in a Community Sample of Older Adults

International Journal of Behavioral Medicine (2014)

-

Socioeconomic status, financial hardship and measured obesity in older adults: a cross-sectional study of the EPIC-Norfolk cohort

BMC Public Health (2013)