Abstract

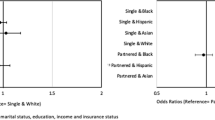

Objective: The purpose of this study was to investigate whether the discordance between women's assessment of the adequacy of the timing of their prenatal care entry and the standard of first trimester initiation was associated with maternal race or ethnicity. Methods: A population-based surveillance system, the California Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, provided data on a stratified random sample of 4,987 women. The women delivered live-born infants from 1994–95 in three perinatal regions. Respondents completed an in-hospital, self-administered questionnaire. Weighted data were analyzed with multiple logistic regression. Results: Twenty-two percent of the women in the sample initiated prenatal care after the first trimester of pregnancy (n = 1,097). Among the women with untimely care, 57% (n = 591) were satisfied with the time of care initiation. Discordance between the women's perception of the adequacy of the time of care initiation and the public health standard of first trimester initiation was associated with maternal ethnicity. After controlling for potential confounders, Mexican-born women with untimely care were more likely to report being satisfied with the time of initiation than were white non-Latina women with untimely care (OR = 4.03, CI = 2.46, 6.59). Conclusions: The design of public health interventions to increase the timeliness of prenatal care initiation will require a greater understanding of pregnant women's own perceptions of their needs for prenatal care, and the differences in perceptions across ethnic groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Institute of Medicine. The effectiveness of prenatal care. In: Preventing low birthweight. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1985:132–49.

Merkatz R, Thompson E, editors. New perspectives on prenatal care. New York: Elsevier, 1990:6.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Objectives for improving health and tracking Healthy People 2010.Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, Nov 2000.

Institute of Medicine. Prenatal care: Reaching mothers, reaching infants.Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1988.

McCormick MC, Brooks-Gunn J, Shorter T, Holmes JH, Wallace CY, Heagarty MC. Outreach as case finding: Its effect on enrollment in prenatal care. Med Care 1989;27:103–11.

Goldenberg RL, Patterson ET, Freese MP. Maternal demographic, situational and psychosocial factors and their relationship to enrollment in prenatal care: A review of the literature. Women Health 1992;19(2/3):133–47.

St. Clair PA, Smeriglio VL, Alexander CS, Connell FA, Niebyl JR. Situational and financial barriers to prenatal care in a sample of low-income inner-city women. Public Health Rep 1990;105:264–7.

Ingram DD, Makuc D, Kleinman JC. National and state trends in use of prenatal care, 1970-83. Am J Public Health 1986;76(4):415–23.

Cramer JC. Social factors and infant mortality: Identifying high-risk groups and proximate causes. Demography 1987;24(3):299–322.

Harvey SM, Faber KS. Obstacles to prenatal care following implementation of a community-based program to reduce financial barriers. Fam Plann Perspect 1993;25(1):32–6.

Braveman P, Bennett T, Lewis C, Egerter S, Showstack J. Access to prenatal care following major Medicaid eligibility expansions. JAMA 1993;269(10):1285–9.

Guyer B. Medicaid and prenatal care. Necessary but not sufficient. JAMA 1990;64(17):2264–5.

Dubay LC, Kenney GM, Norton SA, Cohen BC. Local responses to expanded Medicaid coverage for pregnant women. Milbank Q 1995;73(4):535–63.

Piper JM, Ray WA, Griffin MR. Effects of Medicaid eligibility expansion on prenatal care and pregnancy outcome in Tennessee. JAMA 1990;264(17):2219–23.

Greenberg RS. The impact of prenatal care in different social groups. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1983;145(7):797–801.

Sable MR, Stockbauer JW, Schramm WF, Land GH. Differentiating the barriers to adequate prenatal care in Missouri, 1987-88. Public Health Rep 1990;105(6):549–55.

Ventura SJ. Maternal and infant health characteristics of birth to U.S. and foreign born Hispanic Mothers. Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics, 1994, Xerox.

LaViest TA, Keith VM, Gutierrez ML. Black/white differences in prenatal care utilization: An assessment of predisposing and enabling factors. Health Serv Res 1995;30(1):43–58.

Moore P, Hepworth JT. Use of perinatal and infant health services by Mexican-American Medicaid enrollees. JAMA 1994;272(4):297–304.

Miller MK, Clarke LL, Albrecht SL, Farmer FL. The interactive effects of race and ethnicity and mother's residence on the adequacy of prenatal care. J Rural Health 1996;12(1):6–18.

Albrecht S, Miller M. Hispanic subgroup differences in prenatal care. Soc Biol 1996;43(12):38–58.

Kay MA. Health and illness in a Mexican-American barrio. In: Spicer EH, editor. Ethnic medicine in the southwest. Tucson AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1977:99–166.

Poma PA. Pregnancy in Hispanic women. J Nat Med Associ 1987;79:929–35.

Meikle SF, Orleans M, Leff M, Shain R, Gibbs RS. Women's reasons for not seeking prenatal care: Racial and ethnic factors. Birth 1995;22(2):81.

Solis JM, Marks G, Garcia M, Shelton D. Acculturation, access to care, and use of preventive services by Hispanis: Findings from HHANES 1982-84. Am J Public Health 1990; 80(Suppl):11–19.

Portes A, Kyle D, Eaton WW. Mental illness and help-seeking behavior among Mariel Cuban and Haitian refugees in south Florida. J Health Soc Behav 1992;33(4):283–98.

Balcazar H, Aoyama C, Cai X. Interpretive views of Hispanics' perinatal problems of low birth weight and prenatal care. Public Health Rep 1991;107(4):420–6.

Berube E, Chavez G, Stephenson P, Anderson T. Perinatal risk profile of California women: Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) 1994. Maternal and Child Health Branch California Department of Health Services, March 1997.

Survey Data Analysis. Version 7.5. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute, 1997.

Bender D, Castro D. Explaining the birth weight paradox: Latina immigrants' perceptions of resilience and risk. J Immigrant Health 2000;2(3):155–73.

Baker DW, Hayes R, Fortier JP. Interpreter use and satisfaction with interpersonal aspects of care for Spanish-speaking patients. Med Care 1998;36(10):1461–70.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sarnoff, R., Adams, E. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Discordance Between Women's Assessment of the Timing of Their Prenatal Care Entry and the First Trimester Standard. Matern Child Health J 5, 179–187 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011348018061

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011348018061