Abstract

Objectives

To examine whether women whose partners are involved in their pregnancy are more likely to receive early prenatal care and reduce cigarette consumption over the course of the pregnancy. This study also examines sociodemographic predictors of father involvement during pregnancy.

Methods

Data on 5,404 women and their partners from the first wave of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort (ECLS-B) were used to examine the association between father involvement during pregnancy and maternal behaviors during pregnancy. Multivariate linear and logistic regression analyses were used and data were weighted to account for the complex survey design of the ECLS-B.

Results

Women whose partners were involved in their pregnancy were 1.5 times more likely to receive prenatal care in the first trimester and, among those who smoked at conception, to reduce their cigarette consumption 36% more than women whose partners were not involved in the pregnancy (p = .09). Fathers with less than a high school education were significantly less likely to be involved in their partner’s pregnancy, while first-time fathers and fathers who reported wanting the pregnancy were significantly more likely to be involved.

Conclusions

The positive benefits of father involvement often reported in the literature on child health and development can be extended into the prenatal period. Father involvement is an important, but understudied, predictor of maternal behaviors during the prenatal period, and improving father involvement may have important consequences for the health of his partner, her pregnancy, and their child.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Until recently, fathers’ involvement in their children’s lives had been a neglected area of research; only approximately 10 years ago was the issue of fatherhood considered an important issue of federal study. However, with the development of the Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics in 1994, there has been a fundamental shift in the focus on research, programs and policies related to fatherhood. This Federal interagency collaboration helped to promote government-wide initiatives to: ensure that policies and programs include fathers; modify programs directed at women and children to encourage father involvement; measure the success of programs that involve father involvement; and include fathers in government-related research regarding children and families [1].

Current research has established associations between father involvement and a host of child outcomes including early learning capacities, academic achievement, psychological outcomes, and behavior [2–7]. Although fathers have traditionally been seen primarily as financial providers [8], it is clear that they also serve in numerous other capacities including caregiver, playmate, teacher and role model. In addition to being actively involved in children’s lives, fathers also provide significant resources and emotional support to mothers, which is particularly beneficial during the prenatal period.

For mothers, higher levels of perceived support from their partners in the form of emotional closeness, intimacy, and greater perceived equity is associated with lower emotional distress [9, 10]. Further, women who view their partner as not dependable or lacking in financial, emotional and instrumental support are also more likely to view their pregnancy as unwanted [11]. This, in turn, is associated with delays in prenatal care, and a reduced likelihood that the mother will reduce her consumption of alcohol or cigarettes during pregnancy [12, 13]. Related to these findings is research suggesting that married and cohabiting women were significantly more likely to attain prenatal care and decrease drug and cigarette use than those who lived apart but remained romantic [14].

Despite increasing interest in father involvement in recent decades, limited research has examined sociodemographic characteristics that predict father involvement during childhood, and none have examined predictors of involvement during the prenatal period. However, limited research does suggest that fathers with higher educational attainment [3, 4, 7, 15], fathers with a stable employment history [8, 16], younger fathers [17], white fathers [15], and fathers who are married to the mother [14] are more likely to be involved in their children’s lives. It is not clear, however, whether similar characteristics will predict father involvement during the prenatal period. While no studies to our knowledge have examined father’s pregnancy intention as a predictor of subsequent father involvement, one study found that women whose partners wanted the pregnancy were more likely to receive timely prenatal care [18], suggesting that pregnancy intention may be an important predictor of father involvement during pregnancy.

The current study examines the influence of father involvement during pregnancy on two maternal behaviors important to a successful pregnancy and a healthy baby: accessing early prenatal care and reducing the number of cigarettes smoked during the prenatal period. We hypothesize that father involvement during pregnancy will positively influence maternal prenatal health behaviors, above and beyond maternal characteristics alone, and that women who have husbands or partners who are involved in the pregnancy will be more likely to receive early prenatal care, and, among mothers who smoked at conception, will be more likely to reduce the amount of cigarettes smoked during pregnancy. We also examine predictors of father involvement during pregnancy and hypothesize that fathers with a higher educational attainment, who are employed, are older, white, married to the mother, and report wanting the pregnancy at the time of conception will be more likely to be involved in their partner’s pregnancy.

Methods

Study Sample

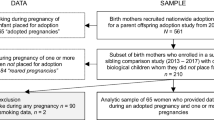

Data for the present study come from the first wave of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), which is following a nationally representative cohort of children born in 2001 with a focus on their health, development, care, and education. The sample was selected from birth certificates received through the National Center for Health Statistics vital statistics system from 46 states and the District of Columbia. All children born in 2001 were eligible to participate except those born to mothers under the age of 15, or those who died or were adopted before they were 9 months of age [19].

The first wave of data collection occurred when the child was 9 months of age. Parents completed an interview, direct child assessments were performed, and additional data were collected from birth certificates, child care providers, and schools to provide information on multiple aspects of child development, family processes and health outcomes. Of those selected for participation in the ECLS-B, 70.8% completed the parent interview [19]. In addition to the interview, both resident and non-resident fathers completed a self-administered questionnaire. However, information about involvement during pregnancy was obtained from residential (76.1% response rate), but not non-residential fathers [19]. Therefore, our analytic sample is limited to 5,404 biological mothers who resided with the biological father at the start of the study, and who had a partner who completed the resident father survey.

Measures

Father involvement

Fathers reported on their involvement in the pregnancy through self-administered questionnaires. Involvement was derived from six father-reported items that assessed various types of involvement during the prenatal period [20]. Items included whether the father discussed the pregnancy with spouse; saw a sonogram/ultrasound; listened to baby’s heartbeat; felt baby move; attended childbirth or Lamaze classes; and bought things for the baby. For each item, fathers indicated any involvement (yes/no). The six items were summed to create a scale score that ranged from zero to six. Higher scores denote more involvement. Fathers with invalid or missing data on more than one of the six items were not included in analyses. For the purposes of this study, a dichotomous measure of father involvement was created where fathers with a score of 5 or higher were considered to be involved in the pregnancy, as this score requires that fathers be involved in their partner’s pregnancy in more than one setting (e.g. home and physician’s office, or home and childbirth class) and indicates a higher level of involvement than participation in the home setting alone.

Maternal prenatal behaviors

Prenatal care was obtained from the birth certificate and supplemented by parent report of the initiation and receipt of any prenatal care in the event that birth certificate data were not available. Mothers who initiated care in the 1st trimester were considered to have received early prenatal care.

Mothers reported the average number of cigarettes smoked per day in the 3 months prior to conception, and in the 3 months prior to birth. Mothers who reported smoking fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime were considered nonsmokers at both time points. The percent change in mother’s cigarette consumption over the course of pregnancy was derived by dividing the average number of cigarettes smoked in the 3 months prior to their child’s birth by the average number of cigarettes smoked in the 3 months prior to conception, subtracting this ratio from 1.0, and multiplying the difference by 100.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Characteristics of both mothers and fathers were obtained by self-report and included educational attainment (less than high school, high school diploma/equivalent, vocational/tech school or some college, BA or higher), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Other), employment at 9 months (full-time, part-time, unemployed), family income in the past year (less than $20,000, $20,001–35,000, $35,001–50,000, $50,001 or higher), marital status (married, cohabiting, single) and number of previous live births (father). Maternal parity and parent age (less than 20 years old, 20–29 years old, or 30 or more years old) at the time of birth were obtained from birth certificate data.

Pregnancy intention

Pregnancy intention was a composite measure based on retrospective self-reports of the mother and the father indicating whether the mother and father wanted the pregnancy at the time they became pregnant. A four-level variable was created indicating that they both wanted the pregnancy, only the mother wanted the pregnancy, only the father wanted the pregnancy, and neither the mother nor the father wanted the pregnancy.

Analyses

Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess both the relationship between father involvement and receipt of early prenatal care, as well as the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics and father involvement. These analyses were conducted using the RLOGIST procedure in SUDAAN, version 8.0, and were weighted to account for the complex survey design of the ECLS-B. Multivariate linear regression using the REGRESS procedure in SUDAAN, again with weighted data, was used to assess the relationship between father involvement and percent reduction in cigarette smoking. All models controlled for relevant sociodemographic characteristics of the mother (predicting prenatal care and percent reduction in cigarette smoking) and the father (predicting father involvement).

Results

The majority of the analytic sample were white, married, had a household income above $50,000 a year, and had at least some college or vocational school with approximately 36% of both mothers and fathers completing a bachelors degree or higher (see Table 1). Approximately half of mothers and fathers were over the age of 30 at the time of their child’s birth and 60% had previous children. Over 86% of fathers worked full time, while close to half of mothers were not working at the time of the survey. The percent reduction in cigarette smoking ranged from 0% (mother did not decrease cigarette consumption) to 100% (mother quit smoking). Thirty-six mothers, however, increased their percent consumption of cigarettes smoked over the course of pregnancy, which ranged from a 25% to a 1,900% increase.

Table 2 presents the association between father involvement during pregnancy and the mother’s receipt of early prenatal care. As shown in Table 2, women whose partners were involved in the pregnancy were approximately one and a half times more likely to receive prenatal care in the first trimester (OR = 1.42, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.99), after controlling for both maternal sociodemographic characteristics and pregnancy intention status. Consistent with existing literature, women with less than a high school education, Hispanic and Asian women, and those who are cohabiting, rather than married to the father were significantly less likely to receive prenatal care in the first trimester, while women with a higher household income were significantly more likely to receive early prenatal care. As expected, pregnancy intention status was also a strong predictor of receiving prenatal care in the first trimester, as women were half as likely to receive early care if neither parent wanted the pregnancy at the time of conception (OR = .53, 95%CI: .37, .94).

The association between father involvement and percent reduction in cigarette smoking are presented in Table 3. Among women who smoked at conception (n = 1,076), those who had involved partners reduced their cigarette consumption 36% more than women whose partners were not involved in the pregnancy (p = .09). However, women with less than a high school education were significantly less likely to reduce their percent consumption relative to those with a college degree or higher, and Hispanic and Asian mothers were more likely to reduce cigarette consumption compared to White mothers. Women with one or more previous children were also more likely to reduce percent consumption of cigarettes over the course of pregnancy.

Given that father involvement is a significant predictor of receiving early prenatal care, and is associated with a significant reduction in cigarette smoking during pregnancy, we examined whether certain characteristics of the father were associated with involvement during the prenatal period. As hypothesized, two of the strongest predictors were paternal education and pregnancy intention status (Table 4). Fathers with less than a high school diploma were less than half as likely to be involved in the pregnancy than fathers with a college degree or higher (OR = 0.45, 95%CI: 0.31, 0.65). With regard to intention status, fathers were significantly more likely to be involved in the pregnancy if they reported wanting the pregnancy at the time of conception, and interestingly, were most likely to be involved if they, and not their partner, wanted the pregnancy. Compared to neither parent wanting the pregnancy, when both parents wanted the pregnancy, fathers were about 1.4 times more likely to be involved (95%CI: 1.06, 1.95), while when only the father reported wanting the pregnancy, he was 1.7 times more likely to be involved (95%CI: 1.14, 2.51). Fathers were also significantly more likely to be involved if this was their first child.

However, other characteristics including current employment, age, and marital status were not associated with father involvement as hypothesized. Further, while Hispanic men were significantly less likely to be involved during the prenatal period (OR = .52, 95%CI: .39, .69) when compared to white fathers, there were no other differences in father involvement by race or ethnicity.

Discussion

This study is one of the first to extend the positive influence that father involvement has on the health of his family into the prenatal period. Women whose partners were involved in their pregnancy were significantly more likely to receive prenatal care in the first trimester (OR = 1.42, 95%CI: 1.01, 1.99), and, among women who smoked at conception, those whose partners were involved in their pregnancy reduced their cigarette consumption 36% more than women whose partners were not involved.

Logistic regression models predicting father involvement suggested that fathers with less than a high school diploma were significantly less likely to be involved in their partner’s pregnancy, while new fathers (having their first child) and fathers who wanted the pregnancy were significantly more likely to be involved in the pregnancy, regardless of whether the mother wanted the pregnancy.

While this study suggests that a father’s involvement in his partner’s pregnancy is beneficial for the health of the pregnancy and his future child by increasing the likelihood of early prenatal care and in reducing cigarette smoking during pregnancy, several limitations of this study are worth noting. First, data on several key variables including intention status, and cigarette smoking at conception and birth were reported retrospectively when the child was 9 months of age, and may be subject to recall bias. However, our measure of pregnancy intention is associated with receipt of prenatal care in the expected direction, lessening this concern. Further, since unwanted pregnancies are most likely to be under-reported after the child is born (e.g. parents don’t admit not wanting the child at time of conception) [21], the association between intention status and prenatal care is likely biased towards the null.

Retrospective reporting of smoking status is of greater concern, however, and recall bias either by under-reporting the number of cigarettes smoked at conception or birth, or over-reporting the reduction in cigarettes smoked over the course of the pregnancy may be contributing to the non-significant association between father involvement and percent reduction in cigarette smoking. However, given that women whose partners were involved in their pregnancy were more likely to reduce the number of cigarettes smoked over the course of pregnancy, this issue deserves further study.

Finally, it should be noted that this study is cross-sectional in nature and included only resident fathers. Results of this study cannot be generalized to non-resident fathers (i.e. those who were not residing with their partner at the time of the interview). Therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution, as this may explain why marital status was not significantly associated with involvement during pregnancy. Results of this study should be replicated to identify whether similar patterns of association exist for fathers who are not living with the mother.

Strengths of this study include its large, national sample of women and their partners, and use of birth certificate data for one of our key outcomes of interest, prenatal care. It should be noted, however, that while this sample is comprised of mothers of a nationally representative sample of children born in 2001, it is not representative of all mothers or reproductive-age women in the U.S. Compared to all women who gave birth from June 2001 to June 2002, our analytic sample was, on average, older, had a higher level of education, and a higher family income [22]. Therefore, additional research on father involvement during pregnancy is needed among families of lower socioeconomic position, where women may be more likely to smoke during pregnancy or have late initiation of prenatal care.

Including pregnancy intention status as a combination of both mother and father intention is a further strength of this study as intention status is often limited to the mother and is not always included in models predicting behaviors during the prenatal period. Inclusion of parental intention status allows for an examination of the influence of parental involvement during pregnancy on two important prenatal behaviors, receipt of prenatal care and cigarette smoking, regardless of whether the mother or father wanted the pregnancy. Further, including a measure of intention status in the model predicting father involvement illustrated the importance of a father wanting the pregnancy, regardless of whether his partner feels the same.

Results of this study suggest that the positive benefits of father involvement often reported in the literature on child health and development can be extended into the prenatal period. Future research is needed to further validate these findings, particularly with longitudinal data, and to test whether father involvement during the prenatal period has long-term outcomes for both the mother and the child once the child is born. Programs aimed at improving father involvement in children’s lives may be extended to include the importance of being involved during the prenatal period, particularly for men who are likely to become fathers again. This may be particularly beneficial as our results show that fathers who already have at least one child are significantly less likely to be involved in the pregnancy than first-time fathers. Finally, our findings reiterate the importance of family planning, as fathers who wanted the pregnancy were significantly more likely to be involved in their partner’s pregnancy. Overall, findings from this study suggest the importance of father involvement during the prenatal period for the health of his partner, her pregnancy, and ultimately, their child.

References

Clinton, W. J. (1995). Supporting the role of fathers in families. Washington D.C.: Memorandum for the heads of executive departments and agencies.

Deutsch, F. M., Servis, L. J., & Payne, J. D. (2001). Paternal participation in child care and its effects on children’s self-esteem and attitudes toward gendered roles. Journal of Family Issues, 22, 1000–1024.

Cooksey, E. C., & Fondell, M. M. (1996). Spending time with his kids: Effects of family structure on fathers’ and children’s lives. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 693–707.

Amato, P. R., & Rivera, F. (1999). Paternal involvement and children’s behavior problems. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 375–384.

Fagan, J., & Iglesias, A. (1999). Father involvement program effects on fathers, father figures, and their Head Start children: A quasi-experimental study. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 14, 243–269.

Nord, C. W., Brimhall, D., & West, J. (1997). Fathers’ involvement in their children’s schools. Washington D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics.

Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Shannon, J. D., Cabrera, N. J., & Lamb, M. E. (2004). Fathers and mothers at play wtih their 2- and 3-year-olds: Contributions to language and cognitive development. Child Development, 75, 1806–1820.

Ray A., Hans S. (1996). Caregiving and providing: The effect of paternal involvement of urban low-income African American fathers on parental relations. In: The Demographic and Behavioral Sciences Branch and the Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Branch of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development tFIFoCa, ed. Conference on Developmental, Ethnographic, and Demographic Perspectives on Fatherhood. Bethesda, MD.

Rini, C., Schetter, C. D., Hobel, C. J., Glynn, L. M., & Sandman, C. A. (2006). Effective social support: Antecedents and consequences of partner support during pregnancy. Personal Relationships, 13, 207–229.

Cutrona, C. E. (1996). Social support as a determinant of marital quality: The interplay of negative and supportive behaviors. In: Pierce G. R, Sarason B. R, & Sarason IG (eds.), Handbook of social support and the family. New York: Plenum Press.

Kroelinger, C. D., & Oths, K. S. (2000). Partner support and pregnancy wantedness. Birth, 27, 112–119.

Hellerstedt, W. L., Pirie, P. L., & Lando, H. A. et al. (1998). Differences in preconceptional and prenatal behaviors in women with intended and unintended pregnancies. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 663–666.

Kost, K., Landry, D. J., & Darroch, J. E. (1998). Predicting maternal behaviors during pregnancy: Does intention status matter? Family Planning Perspectives, 30, 79–88.

Teitler, J. O. (2001) Father involvement, child health, and maternal health behavior. Children and Youth Services Review, 23, 403–425.

Yeung, W. J., Sandberg, J. F., Davis-Kean, P. E., & Hofferth, S. L. (2001). Children’s time with fathers in intact families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 63, 136–154.

Coley, R. L., & Chase-Lansdale, P. L. (1999). Stability and change in paternal involvement among urban African American fathers. Journal of Family Psychology, 13, 416–435.

Ekeus, C., & Christensson, K. (2003). Reproductive history and involvement in pregnancy and childbirth of fathers of babies born to teenage mothers in Stockholm, Sweden. Midwifery, 19, 87–95.

Sangi-Haghpeykar, H., Mehta, M., Posner, S., & Poindexter, A. R. (2005) Paternal influences on the timing of prenatal care among Hispanics. Maternal Child Health Journal, 9, 159–163.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2004). User’s manual for the ECLS-B nine-month restricted-use data file and electronic code book. Washington, DC.

Bronte-Tinkew J., Carrano J., Guzman L. (2006). Fathers’ perceptions of their roles, socio-demographic correlates and links to involvement with infants. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research and Practice about Men as Fathers, 4(3), 254–285.

Sable, M. R. (1999). Pregnancy intentions may not be a useful measure for research on maternal and child health outcomes. Family Planning Perspectives, 31, 249–250.

US Census Bureau. (2002). Fertility of American women current population survey—June 2002 detailed tables. Census Bureau Population Division Fertility & Family Statistics Branch.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD046123–01) to Dr. Elizabeth C. Hair, Ph.D and Dr. Tamara Halle, Ph.D.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, L.T., McNamara, M.J., Milot, A.S. et al. The Effects of Father Involvement during Pregnancy on Receipt of Prenatal Care and Maternal Smoking. Matern Child Health J 11, 595–602 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-007-0209-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-007-0209-0