Abstract

There is a growing concern that some youth are overscheduled in extracurricular activities, and that this increasing involvement has negative consequences for youth functioning. This article used data from the Educational Longitudinal Study (ELS: 2002), a nationally representative and ethnically diverse longitudinal sample of American high school students, to evaluate this hypothesis (N = 13,130; 50.4% female). On average, 10th graders participated in between 2 and 3 extracurricular activities, for an average of 5 h per week. Only a small percentage of 10th graders reported participating in extracurricular activities at high levels. Moreover, a large percentage of the sample reported no involvement in school-based extracurricular contexts in the after-school hours. Controlling for some demographic factors, prior achievement, and school size, the breadth (i.e., number of extracurricular activities) and the intensity (i.e., time in extracurricular activities) of participation at 10th grade were positively associated with math achievement test scores, grades, and educational expectations at 12th grade. Breadth and intensity of participation at 10th grade also predicted educational status at 2 years post high school. In addition, the non-linear function was significant. At higher breadth and intensity, the academic adjustment of youth declined. Implications of the findings for the over-scheduling hypothesis are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This is the mean total number of activities for the full range of activities (0–24). The mean number of activities is slightly lower for the 10-activity cap measure (M = 2.55, SD = 2.34).

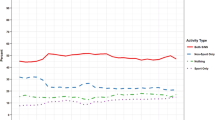

Figure 1 presents the means by breadth of participation at 10th grade for youth who had average grade point average at 10th grade, had parents with average levels of education, and had families with average income.

Figure 2 presents the means by intensity of participation at 10th grade for youth who had average grade point average at 10th grade, had parents with average levels of education, and had families with average income.

References

Arbuckle, J. L. (1996). Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In G. A. Marcoulides & R. E. Schumacker (Eds.), Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques (pp. 243–277). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Best, J. R., & Miller, P. H. (2010). A developmental perspective on executive function. Child Development, 81, 1641–1660. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01499.x.

Bohnert, A., Fredricks, J. A., & Randall, E. (2010). Comparing unique dimensions of youths’ organized activity involvement: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Review of Educational Research, 4, 576–610. doi:10.3102/0034654310364533.

Busseri, M. A., Rose-Krasnor, L., Willoughby, T., & Chalmers, H. (2006). A longitudinal examination of breadth and intensity of youth activity involvement and successful development. Developmental Psychology, 42, 1313–1326. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1313.

Coleman, J. S. (1961). The adolescent society. New York: Free Press of Glencoe.

Cooper, H., Valentine, J. C., Nye, B., & Lindsay, J. J. (1999). Relationships between five after-school activities and academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 9, 369–378. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.91.2.369.

Côté, J., Baker, J., & Abernethy, B. (2003). From play to practice: A developmental framework for the acquisition of expertise in team sports. In J. Starkes & K. A. Ericsson (Eds.), Expert performance in sports: Advances in research on sport expertise (pp. 89–110). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Covay, E., & Carbonaro, W. (2010). After the bell: participation in extracurricular activities, classroom behavior, and academic achievement. Sociology of Education, 83, 20–45. doi:10.1177/0038040709356565.

Dahl, R. E. (1999). The consequences of insufficient sleep for adolescents: Link between sleep and emotional regulation. Phi Delta Kappan, 80, 354–359.

Darling, N. (2005). Participation in extracurricular activities and adolescent adjustment: Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 493–505. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-7266-8.

Eccles, J. S., & Gootman, J. A. (Eds.). (2002). Community programs to promote youth development. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press.

Elkind, D. (2001). The hurried child: Growing up too fast, too soon. Cambridge, MA: DA Capa Press.

Farkas, G. (2003). Cognitive skills and noncognitive traits and behaviors in the stratification process. Annual Review of Sociology, 29, 542–562. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100023.

Feldman, A. F., & Matjasko, J. L. (2005). The role of school-based extracurricular activities in adolescent development: A comprehensive review and future directions. Review of Educational Research, 75, 159–210. doi:10.3102/00346543075002159.

Finn, J. D. (1989). Withdrawing from school. Review of Educational Research, 59, 117–142. doi:10.3102/00346543059002117.

Fredricks, J. A. (2011). Commentary: Extracurricular activities: An essential aspect of education. Teachers College Record. Retrieved at http://www.tcrecord.org/Content.asp?ContentId=16414.

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2005). Developmental benefits of extracurricular involvement: Do peer characteristics mediate the link between activities and youth outcomes? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 6, 507–520. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-8933-5.

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2006). Is extracurricular participation associated with beneficial outcomes: Concurrent and longitudinal relations? Developmental Psychology, 42, 698–713. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.698.

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2010). Breadth of extracurricular participation and adolescent adjustment among African American and European American youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 2, 307–333. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00627.x.

Gilbert, S. (1999). For some children, it’s an after-school pressure cooker. New York Times, 7.

Hansen, D. M., Larson, R. W., & Dworkin, J. B. (2003). What adolescents learn in organized youth activities: A survey of self-reported developmental experiences. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13, 25–55. doi:10.1111/1532-7795.1301006.

Holland, A., & Andre, T. (1987). Participation in extracurricular activities in secondary school: What is known, what needs to be known? Review of Educational Research, 57, 437–466.

Ingels, S. J., Pratt, D. J., Wilson, D., Burns, L. J., Currivan, D., Roger, J. E., et al. (2007). Education longitudinal study of 2002: Base-year to second follow-up data file documentation (NCES 2008–347). Washington, DC: US Department of Education.

Jordan, W. J., & Nettles, S. M. (2000). How students invest their time outside of school: Effects on school-related outcomes. Social Psychology of Education, 3, 217–243.

Larson, R. W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist, 55, 170–183. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.170.

Linville, P. W. (1985). Self-complexity and affective extremity: Don’t put all of your eggs in one cognitive basket. Social Cognition, 3, 94–120. doi:10.1621/soco.1985.3.1.94.

Luthar, S. S., & Sexton, C. (2004). The high price of affluence. In R. V. Kail (Ed.), Advances in child development (Vol. 32, pp. 126–162). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Luthar, S. S., Shoum, K. A., & Brown, P. J. (2006). Extracurricular involvement among affluent youth: A scapegoat for “Ubiquitous Achievement Pressures”. Developmental Psychology, 42, 583–597. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.3.583.

Mahoney, J. L., & Cairns, R. B. (1997). Do extracurricular activities protect against early school dropout? Developmental Psychology, 33, 241–253. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.95.2.409.

Mahoney, J. L., Cairns, B. D., & Farmer, T. (2003). Promoting interpersonal competence and educational success through extracurricular activity participation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 409–418. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.95.2.409.

Mahoney, J. L., Harris, A. L., & Eccles, J. S. (2006). Organized activity participation, positive youth development, and the over-scheduling hypothesis. Society for Research in Child Development: Social Policy Report, 20, 1–30.

Mahoney, J., Vandell, D. L., Simpkins, S., & Zarrett, N. (2009). Adolescent out-of-school activities. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (3rd ed., pp. 228–269). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Marsh, H. W. (1992). Extracurricular activities: Beneficial extension of the traditional curriculum or subversion of academic goals. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84, 553–562. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.84.4.553.

Marsh, H. W., & Kleitman, S. (2002). Extracurricular school activities: The good, the bad, and the non-linear. Harvard Educational Review, 72, 464–514.

Melman, S., Little, S., & Akin-Little, A. (2007). Adolescents overscheduling: the relationships between levels of participation in scheduled activities and self-reported clinical symptomology. High School Journal, 2, 18–30. doi:10.1353/hsj.2007.0011.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2010). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthén.

Noonan, D. (2001). Stop stressing me: For a growing number of kids, the whirlwind of activities can be overwhelming. How to spot burnout. Newsweek, 54–55.

Rose-Krasnor, L., Busseri, M. A., Willoughby, T., & Chalmers, H. (2006). Breadth and intensity of youth activity involvement as contexts for positive development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 385–499. doi:10.1007/10964-006-9037-6.

Rosenfeld, A., & Wise, N. (2000). The overscheduled child: Avoiding the hyper-parenting trap. New York: St. Martin’s Press Griffin.

Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147.

Shaw, S., Caldwell, L. L., Kleiber, D., & Douglas, A. (1996). Boredom, stress, and social control in daily activities of adolescents. Journal of Leisure Research, 28, 274–292.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the American Educational Research Association which receives funds for its “AERA Grants Program” from the National Science Foundation and the National Center for Education Statistics of the Institute of Education Sciences (US Department of Education) under NSF Grant #DRL-0634035. A special thanks to Amy Bohnert for helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Opinions reflect those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the granting agencies.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fredricks, J.A. Extracurricular Participation and Academic Outcomes: Testing the Over-Scheduling Hypothesis. J Youth Adolescence 41, 295–306 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9704-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9704-0