Abstract

While community mobilisation (CM) is increasingly advocated for HIV prevention, its impact on measurable outcomes has not been established. We performed a systematic review of the impact of CM within HIV prevention interventions (N = 20), on biomedical, behavioural and social outcomes. Among most at risk groups (particularly sex workers), the evidence is somewhat consistent, indicating a tendency for positive impact, with stronger results for behavioural and social outcomes than for biomedical ones. Among youth and general communities, the evidence remains inconclusive. Success appears to be enhanced by engaging groups with a strong collective identity and by simultaneously addressing the socio-political context. We suggest that the inconclusiveness of the findings reflects problems with the evidence, rather than indicating that CM is ineffective. We discuss weaknesses in the operationalization of CM, neglect of social context, and incompatibility between context-specific CM processes and the aspiration of review methodologies to provide simple, context-transcending answers.

Resumen

Mientras que la movilización de la comunidad (MC) es cada vez más recomendada para la prevención del VIH, su impacto en resultados mensurables no se ha establecido. Realizamos una revisión sistemática del impacto de la MC en intervenciones para la prevención del VIH (N = 20), en resultados biomédicos, conductuales y sociales. En grupos de riesgo (particularmente trabajadoras sexuales) la evidencia es más bien consistente, indicando una tendencia general de impacto positivo, siendo los resultados conductuales y sociales más robustos que los biomédicos. En los jóvenes y comunidades en general la evidencia no es concluyente. Resultados favorables parecen ser mejorados al involucrar grupos con una fuerte identidad colectiva y, simultáneamente, atender al contexto socio-político. Proponemos que la naturaleza poco concluyente de los hallazgos refleja problemas con la evidencia, en lugar de sugerir que la MC es inefectiva. Discutimos las debilidades en la operacionalización de la MC, la desatención al contexto social y la incompatibilidad entre procesos contextualmente específicos en la MC y la pretensión de las metodologías de revisión de proveer respuestas simples y que trasciendan el contexto.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many HIV intervention programmes have disappointing outcomes, often ascribed to a lack of community ‘buy-in’. It is often the case that outsiders such as academics, multilateral agencies, or international organisations implement interventions without assessing their relevance to their particular target community. Social research has documented failures of HIV interventions to resonate with local norms, cultures and needs [1, 2]. Behaviours advocated by external health professionals may not be feasible in contexts of poverty, political conflict and gender inequalities [2, 3]. As a result, there is a growing emphasis on the need for community involvement in the planning, implementation and ownership of interventions. Indeed, community mobilisation (CM) is now widely considered a “critical enabler” of an effective HIV/AIDS response [4]. Despite this increasing interest in CM, there has been little systematic attention to its impacts.

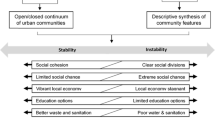

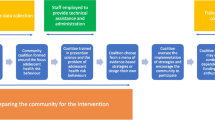

One reason for the lack of systematic attention to CM is that it is used across categories of HIV intervention usually considered separately, namely, biomedical, behavioural and structural interventions. CM has been argued to be valuable in recruiting men to take up circumcision in biomedical interventions [5, 6]. Similarly, in behavioural interventions, CM may be used to recruit participants through outreach, or to inform culturally-appropriate materials [7, 8]. CM is often termed a ‘structural intervention’ when it is considered as a means of empowering marginalised communities and thus changing power relations [9–12]. For a smaller number of studies, CM is considered their main mechanism of intervention [13–16]. Although the impacts of CM have not yet been subject to a systematic review, such a review stands to contribute to research and practice across the range of HIV prevention approaches, wherever CM might be considered a ‘critical enabler’. The term ‘community mobilisation’ is not consistently defined, theorised, operationalized or systematically appraised [17]. In its fullest operationalization, CM seeks “to create and harness the agency of the marginalised groups most vulnerable to HIV/AIDS, enabling them to build a collective, community response, through their full participation in the design, implementation and leadership of health programmes and by forging supportive partnerships with significant groups both inside and outside of the community” [18]. This definition sets a high bar, and many operationalizations of CM are far less ambitious [19]. Although our definition preserves the conceptual distinctiveness of CM, we aimed to be relatively inclusive in this review, for very few published evaluations implement the ‘maximalist’ version of CM as defined above.

For the purposes of this review, we take the term ‘community’ to refer to collective resources that exist among a community, rather than at the individual level. We take the term ‘mobilisation’ to mean capitalising on those community connections and strengths to generate new possibilities of action. In keeping with the ‘minimalist’ definition of CM, in this paper we consider CM as a component of externally-triggered HIV interventions, rather than including indigenous CM initiated by grassroots actors with broader interests than HIV. This latter topic is addressed in the literature on social capital and HIV/AIDS [20–22].

Research on CM to date has tended to be qualitative, grounded in ethnographic methods, and to focus on processes rather than on outcome evaluation [13, 23–25]. A growing body of social research has underscored the role of CM in building HIV competent communities, ensuring interventions are relevant and accessible to local people, and enabling people to work collectively to create health-enabling environments [18, 26, 27]. This work has also emphasised the significance of partnerships between communities and outside agencies as a key supportive condition for effective CM [18, 28, 29]. Furthermore, the pertinence of Western conceptualisations of CM and its constituting elements needs to be validated in specific intervention contexts [17]. Such information is crucial to the appropriate design and evaluation of CM programmes. In the context of the ascendant ‘evidence-based policy and practice’ movements, however, quantitative evaluations, and systematic reviews of these, are valued as sources for informing policy or funding decisions.

The first aim of the current article, therefore, is to present a systematic review of studies of the impacts of CM as a component of complex HIV prevention interventions. The scope of this review is comprehensive in that we do not restrict it to any target group, and we consider the impact on biomedical, behavioural, and social outcome variables. The review draws conclusions about whether CM ‘works’ or not, and delineates more nuanced lessons about the conditions under which CM is more likely to succeed.

A systematic appraisal of the CM intervention literature is challenging. Mobilisation efforts are referred to by many terms (e.g. community solidarity, social mobilisation, community participation, community engagement), which defy simple search strategies. In addition, CM almost invariably constitutes ‘complex interventions’ [30], entailing multiple, indirect pathways between intervention and outcomes. A wide and unresolved debate surrounds the best way to deploy and evaluate CM interventions (CMI) [31, 32], with many arguing that the complex and improvisational nature of good CM defies summary in the linear ‘input–output’ models of change that characterise the ‘gold standard’ approach of randomised controlled trials (RCT). The second aim of the article is to reflect on the methodological challenges of operationalizing, evaluating and reviewing CMI.

Methods

The definition of CM cited above sets a high standard. However, many studies which use the term ‘CM’ do so in a very limited way, for instance using ‘CM’ to simply mean reaching out the community for service or research recruitment. Heeding this concession, our key criterion was that CMI should seek to foster new capacities in a community by facilitating meaningful contact among community members. The reviewed studies aimed to engage communities in one or more of the following: enhancing supportive interpersonal relationships, building within-community support and solidarity (bonding social capital), and building bridges between communities and outside support partners (bridging social capital). In order to do so, interventions employed activities such as setting-up peer support groups and clubs, fostering of community-based organisations, performing dramas, rallies and awareness camps, creating community centres as ‘safe spaces’ for debate and conscientisation, as well as holding multi stake-holder meetings and advocacy. On the methodological front, we included reports on the impact of CM as a component of more complex interventions, and excluded articles where the impact of a singled-out mobilisation activity (e.g. peer group membership) was measured.

The following questions guided the review:

-

To what extent does CM impact on measurable HIV-related prevention outcomes?

-

Is there a significant relationship between the implementation of programmes with a CM component and biomedical, behavioural and social outcomes? If so, what is the direction of this relationship for each outcome?

-

Under what programmatic conditions (target population and intervention components) is CM most successful?

-

What are the methodological challenges of evaluating and synthesising evidence on CM?

Selection

Standard systematic review procedures were followed (Fig. 1). The bibliographic databases SCOPUS, PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and PsycInfo were interrogated using free-text terms to produce a sensitive search, adjusting terms depending on the search tools available (e.g. truncation). Searches included a combination of the following terms: “intervention” AND “hiv OR aids” AND “community mobili*” OR “community particip*” OR “community led” OR “community based” OR “community activit*” OR “community development” OR “capacity building” (full search strings by database in supplementary online information). When possible, irrelevant publication types (e.g. commentaries) were excluded using search tools. A complementary search was carried out through expert consultation and systematic reference screening of previous related reviews [12, 33, 34], which rendered 32 records.

Records identified were systematised and, after removing duplicates, 1096 abstracts were screened. Of these, 97 were selected for full-text retrieval. To be included, articles needed to have been published in English in the last 11 years (from January 2003 to October 2013), and to report studies conducted in low-income, lower-middle-income or upper-middle-income economies [35]. Given that the nature of HIV epidemics, and understandings of CM have changed greatly historically, the timespan was chosen to reflect contemporary research and practice. We used three main inclusion criteria, including studies which:

-

Reported community-based initiatives (as opposed to health facility-based medical interventions) that engaged one or more community groups in concrete participatory activities. Studies should have reported modes of CM that foster meaningful community connections.

-

Evaluated the intervention in terms of at least one quantifiable biomedical (incidence and/or prevalence of HIV-1, HSV-2 and bacterial STI) or behavioural (reported condom use, reported health-service use, and HIV test-taking) outcome.

-

Evaluated outcomes with reference to a comparator or control, irrespective of research design.

The second inclusion criterion is based on the rationale that CM, and derived social outcomes, shapes sexual behaviours, which in turn impact on biomedical indicators. Thus, we targeted the proximal outcomes of this logic model. Although reported condom use has been found to be poorly associated with biomedical markers [36–38], we included condom use as a behavioural outcome because it is a proxy measure of actual sexual risk historically applied in the prevention literature, affording some degree of comparability across studies. Behavioural outcomes were expanded ad-hoc to engagement in extramarital sex for one study [39], on the assumption that this might increase a person’s HIV risk [40]. This study was selected given its careful consideration of community involvement.

To enable the implementation of the selection criteria, and given the diversity of terminology employed, two steps were taken in the selection process. First, during abstract screening, records reporting the same study were clustered together, so as to gather as much information about a study as possible. Second, during full-text vetting, “reference list checking” [41] was performed to aid final selection. Eleven articles were selected from this search and assessed for inclusion.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Twenty unique studies were identified, documented by 28 primary and 18 supplementary articles. When possible, the unit of analysis consisted of studies rather than articles. Bibliographic data were noted for each study, as were methodological details such as sample, control or comparison and intervention components (Table 1). Outcomes identified in each study were classified into biomedical, behavioural and social. Biomedical outcomes reported in included articles addressed incidence and/or prevalence of HIV-1, HSV-2 and bacterial STI. Behavioural outcomes were limited to reported condom use, reported health-service use, and HIV test-taking. Social outcomes, such as collective efficacy or community cohesion, were included only if in a study that also reported at least one biomedical or behavioural outcome. Social outcomes considered any measurement of collectivisation, cohesion, partner violence and/or participation and excluded individualised accounts of personal development, individual empowerment or autonomy. None of the studies reported structural outcomes such as changes in legislation or policy implementation.

Outcomes related to knowledge, attitudes, individual level perceptions (e.g. attitude towards condoms, self-efficacy or individual-level ‘power-within’) were not included, given that knowledge, individual skills and attitudes are not a sound reflection of behaviour [42–44]. Similarly, reported STI were omitted on the basis that an actual measure (incidence/prevalence), rather than a proxy, was more valid. We included results for different types of outcomes if reported in more than one article belonging to the same study. When similar outcomes for the same study were reported by more than one article, we included the results using a larger sample, given that this frequently aggregated the smaller samples reported elsewhere.

Given the heterogeneity of studies in terms of study design, intervention participants and outcomes measurement, a meta-analysis would have been unsuitable for this review. Consequently, the narrative analysis presented below addresses our review questions and, for the second one, relies on both the direction of intervention effects and associations and their reported significance. Furthermore, although studies’ risk of bias did not determine inclusion, we assessed this risk and methodological soundness by using Thomas’s Quality Assessment tool for Quantitative Studies [45]. This instrument is recommended for systematic reviews of health interventions [46] and, while suitable for our review because it evaluates a range of quantitative designs [47], was adapted to accommodate the complexity of studies included (Table 2).

Results

The Studies

Of the corpus of twenty studies, seven were RCT: project Accept [15, 48], the Regai Dzive Shiri intervention [49], the MEMA kwa Vijana trial [50], the Stepping Stones intervention [51], the Manicaland Project [52], the IMAGE project [53], and a trial in the Masaka district, Uganda [54]. Project Accept was carried out simultaneously in Sub-Saharan Africa and South and South East Asia, while the other six trials were implemented in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The remaining twelve studies used various observational designs. In India, South and South East Asia, the RISHTA project [39], the Parivartan project [55, 56], the Avahan project [57–62], the Frontiers Prevention Project (India) [63], a programme by the India HIV/AIDS Alliance [64], as well as a Sonagachi-replication [65, 66] were implemented; in Latin America and the Caribbean, the Encontros project [67], the Princesinha project [68], the Frontiers Prevention Project (Ecuador) [69], a Sonagachi-inspired intervention [70], and a comparison between CM and CM plus policy changes [14] were carried out. Finally, the Carletonville project [71] was undertaken in Sub-Saharan Africa and a participatory intervention was implemented in Chengdu, China [72].

The boundaries of ‘community’ were conceptualised in three main ways by the selected studies. First, in contexts of concentrated HIV epidemics, interventions targeted groups most at risk: ten studies focused on sex workers [14, 56, 59, 63–65, 67–70], four on men who have sex with men (MSM) [57, 63, 69, 72], and one study [39] focused on local heterosexual men whose high levels of alcohol consumption were found to be putting their sexual health at risk [73]. These communities were thus assumed to share a social identity, location and concrete practices (e.g. work and leisure). Second, mainly in contexts of generalised epidemics, youth were targeted by four studies [15, 49–51], treating them also as communities in terms of identity and sexual risks, within geographically-bound communities. Four further studies [52–54, 71] conducted in the generalised epidemic of Sub-Saharan Africa were concerned with mobilising geographically-bound communities by targeting adults or a number of groups (e.g. women who applied for a loan; miners, sex workers and adults simultaneously) within the community. Outcomes were evaluated at the level of participant communities and their comparators, except for four projects (Accept, Avahan, IMAGE and Regai Dzive Shiri), which evaluated the effects of the intervention at the wider community- or population-level.

Do CM Interventions Work? It Depends on for Whom

Since the pattern of findings differs by population, we have divided our presentation of the findings into two sections, reporting first the findings for sex workers and other most at risk groups, and then findings for youth and general communities.

Sex Workers and Other Most at Risk Groups

The first group are mainly sex workers and, to a lesser extent, other most at risk groups such as men who have sex with men (MSM), who have been targeted in contexts of concentrated HIV epidemics. Inconsistent results were reported in the Avahan programme, in which for population effects at state level, “greater intensity” of the intervention was significantly associated with lower HIV prevalence in 3 Indian states, but with very small effect sizes (−0.0026 to −0.0022). The association between CMI and HIV prevalence was non-significant in 3 other states [60–62], although authors acknowledge that the prevalence in chronic diseases such as HIV could require long periods to be apparent. The Frontiers Prevention Project in Ecuador found no significant effects of the intervention on HIV seroprevalence among FSW and MSM [69].

With regards to other STI, a sub-study of the Avahan programme in Karnataka reported that chlamydia and/or gonorrhoea prevalence, and high-titre syphilis, were significantly reduced, while this reduction was non-significant in relation to syphilis among female sex workers (FSW) [61]. Encouragingly, the Frontiers Prevention Project in Andhra Pradesh was associated with lower likelihood of syphilis and HSV-2 among both FSW and MSM [63]. A similar project in Ecuador rendered a significant impact in the reduction of likelihood of syphilis seroprevalence among MSM, while having a borderline effect of lower HSV-2 seroprevalence among FSW in the programme [69]; non-significant programme effects were observed on HSV-2 among MSM and syphilis among FSW [69]. Active participation in the Encontros study was related to a non-significantly lower probability of incident chlamydia and/or gonorrhoea [67], while the Carletonville project rendered a non-significant increase of syphilis, gonorrhoea and chlamydia among participant sex workers [71]. Furthermore, the study in the Dominican Republic [14] found CMI to reduce prevalence of one or more STI (gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis, or chlamydia) among FSW. A further analysis shows that this effect was statistically significant when CM was combined with implementing and enforcing a government policy supporting consistent (100 %) condom use [14]. On the whole, the evidence points to CMI tending to impact on the reduction of STI among sex workers, with this effect being more likely to be significant when CMI is combined with policy interventions [14].

Regarding behavioural outcomes, among sex workers, condom use is the behaviour most addressed, and with the strongest evidence, with various degrees of effect depending on whether sexual encounters are with paying clients, casual or stable partners. Exposure to interventions was found to be significantly associated with increased likelihood of condom use [66], consistent condom use with clients [56], with new clients [14 in Santo Domingo], consistently or during last encounter with regular clients or partners, [14 in Puerto Plata, 61, 63, 67], and for oral sex with clients, in “all situations” and during last week [68]. Other studies have found non-significant or marginal increases related to the intervention, including ever using a condom [71], condom use with last client [63, 70], with all clients [70], with occasional or new clients [14 in Puerto Plata, 61, 67], with non-paying [67] and regular partners [14 in Santo Domingo, 61, 69], as well as for anal and vaginal sex with clients [68]. Marginal decreases in consistent condom use with all partners [70] and casual partners [71] were reported in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and South Africa.

Of note are two behavioural outcomes reported in the interventions with FSW. In the Dominican Republic [14], authors recorded the observed FSW’s verbal rejection of unsafe commercial sex, which increased from pre- to post-intervention in both sites, being significant only for the community where both CM and policy enforcement were implemented. Similarly, in Andhra Pradesh [64], FSW who reported high collectivisation were considerably more likely to procure STI treatment from government health facilities than those who reported low collectivisation, as were those who reported high collective efficacy and collective agency [57]. Collective action, in contrast, was associated with a lower likelihood of STI treatment-seeking [57].

CMI targeting MSM were found to be related to a significant increase in reported condom use with casual and regular sexual partners for vaginal sex, anal sex and oral sex [72] and to the likelihood of condom use with last female partner [63] and last male sexual partner [69]. An association in the same direction was non-significant for condom use with last female partner [69] and last male sexual partner [63]. In one subsample of MSM and transgender people in the Avahan project [57] it was found that participation in a public event was significantly associated with higher likelihood of consistent condom use among paying and non-paying partners, with the same positive trend for collective efficacy, although significant only with paying partners. In the RISHTA intervention [39], which engaged local heterosexual males whose high levels of alcohol consumption were found to put their sexual health at risk, it was reported that changes in extramarital sex were significantly associated to change in alcohol use, so that significant decreases in extramarital sex were observed among men who were drinkers at baseline but non-drinkers at endline.

Social outcomes tended to be positive mainly in terms of community participation and collective identity, with inconsistency in the way social outcomes were measured. Two Sonagachi-inspired programmes found significantly positive changes in social participation [67, 70], but not in perceived social cohesion [67, 70] after intervention in Corumbá [67] and Rio de Janeiro [70], Brazil. Similarly, another Sonagachi adaptation found significant increases in social support through organising and solidarity, but not in political participation in West Bengal, India [65]. An evaluation of the Avahan project, in turn, found that joining a meeting, belonging to a help group and being member of a sex worker collective were significantly associated with higher perceived collective efficacy and higher perceived collective support in non-metropolitan Tamil Nadu, with varying positive effects in the other three settings of Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, in India [59]. A different evaluation report of Avahan also found that collective identity and solidarity were significantly associated with lower odds of violence or abuse by more powerful groups in high-intensity intervention districts, but not in low-intensity ones [58]. In Andhra Pradesh, the study on project Parivartan found a positive relationship between collective identity, collective efficacy and collective agency and programme exposure, which becomes stronger as the level of exposure rises [55].

In sum, there is reasonable evidence for the effectiveness of CMI in reducing STI and increasing condom use among sex workers. Among MSM, there is some evidence that CMI results in increased condom use. Findings regarding social outcomes remain uneven, depending on the social outcome measured. The evidence of CMI effects on HIV prevalence remains limited to projects Avahan and Frontiers Prevention (Ecuador), which provided inconclusive results. It is difficult to draw broad conclusions about which programmatic elements or conditions are most effective (e.g. targeting casual vs. regular partners; working in urban vs. rural areas) because each intervention employed a different design, measured different outcomes, and was conducted in a unique setting.

Youth and General Community

Studies targeting either youth or the general community reported mainly non-significant intervention effects in terms of HIV incidence [51–54] or prevalence at the community level [49, 50]. Project Accept intervention reported lower HIV incidence in intervention than in control communities with borderline statistical significance (p = 0.08) [48]. Similarly, regarding other STI, mainly non-significant effects have been reported for HSV-2 prevalence [49, 50] and incidence [54 for one arm] as well as prevalence of chlamydia, syphilis and gonorrhoea [50, 54 for one arm], while the Carletonville study reported significant increases of chlamydia among miners, men and women, of syphilis among miners and women, and of gonorrhoea among miners [71]. The Masaka trial in Uganda, in turn, found dissimilar results depending on intervention arm: incidence of active syphilis and prevalence of gonorrhoea were significantly lower in one of the intervention arms than in the control group, while HSV-2 incidence was lower in the other intervention arm than in the control group [54]. Only the Stepping Stones programme was associated with a significantly lower HSV-2 incidence in comparison with controls [51]. Hence, there is little evidence that CMI succeed in reducing numbers of HIV and/or STI cases among youth and general communities, with some success limited to the Stepping Stones programme and project Accept.

In terms of behavioural markers, CMI were found to be significantly positively associated with the likelihood of condom use with casual partners [50 in females, 54 in one arm; 71 in miners, men and women] and ever using a condom [71 in miners and women]. However, for a number of interventions no significant changes in either direction were reported on condom use at last sex [49–51], reported ever condom use [54, 71 in men] and condom use with regular [52] and non-spousal [53] partners. For the Manicaland study [52], reported condom use with casual partners was significantly more common in control than in intervention communities. Behaviours other than condom use were also addressed. In the Accept study, the proportion of people taking their first HIV test was significantly larger in community based voluntary counselling and testing communities than in standard care areas [15]. However, the IMAGE project found non-significant differences in having had an HIV test in intervention groups relative to controls [53]. Similarly, in terms of health service use, the Regai Dzive Shiri project had no effect on clinic attendance [49] and the Manicaland project found no intervention-related differences in treatment-seeking within 3 days of STI symptoms [52]. In light of these results, CMI appears to have some effect among youth and targeted communities on condom use with casual partners and promising effects in the uptake of voluntary testing, although evidence for the latter is limited to one study.

Among programmes targeting youth and the general population, evidence of effects on social outcomes is limited to the IMAGE and the Stepping Stones projects. In the former, targeted women reported a significant reduction in intimate partner violence and were more likely to report higher levels of participation in social groups and collective action, than their comparison counterparts, with no significant differences regarding the perception of solidarity and that the community would work together to achieve common aims [53]. In the Stepping Stones programme the proportion of male participants who reported enactment of intimate partner violence was lower than among controls, with this trend maintained across the intervention’s lifetime (p = 0.099, p = 0.054 at 12 and 24 months, respectively), although there was no evidence of this difference among women [51]. Therefore, while these results are promising, there still remain inconsistencies regarding their diffusion into biomedical and behavioural indicators.

In sum, for studies involving youth, targeted groups within communities and geographically-bound communities, no significant results were found for reductions of HIV incidence or prevalence, while marginal impact on the reduction of other STI was identified, mirroring the results of previous reviews [33]. The evidence suggests that while these programmes impact on reported condom use with casual partners, this improvement may not translate into significant changes in biomedical markers. The results obtained for social outcomes are fairly positive but limited to two studies, and hence their relationship with behavioural and biomedical indicators remains to be clarified.

Discussion

The present review has gathered evidence of the effectiveness of interventions with a CM component on biomedical, behavioural and social outcomes. We present our discussion in two sections. The first assesses what can be learnt from our review to inform contemporary CM programming. Given that the findings are generally inconclusive, the second section critically reflects on the literature, to explore reasons for the inconclusiveness of the evidence.

The Systematic Review: What has been Found?

Overall, this systematic review has produced a somewhat inconclusive set of findings. Among sex workers and groups most at risk, the evidence bears some degree of consistency, indicating an overall tendency of positive impact, with more consistent and stronger results for behavioural and social outcomes than for biomedical ones. Among youth and general communities, the evidence of the effects of CMI remains inconclusive. Overall, it is not possible at this point in time to come to a general conclusion as to whether CMI are effective or not, though there is suggestive evidence for sex worker groups. Our review suggests, nonetheless, two more nuanced lessons that may be drawn.

The first is that CMI appear to be more successful with groups who have a meaningful collective identity rather than with more generalised populations. One of the main characteristics of interventions engaging sex workers and groups most at risk is that they capitalise on these groups’ collective identity. CMI often work through their situation of vulnerability to foster mobilisation that is cohesive and fuelled by a need not only to attain HIV-related goals, but also to increase their material and symbolic power and status in the community. Indeed collective identity could arguably have been one of the reasons for success of organic forms of CM efforts such as Sonagachi [74].

One explanation for the different approach in these programmes is that young people and general communities do not evidently display the extreme and conspicuous disadvantages of sex workers and thus do not appear in need of tackling the social determinants of their problems. It is plausible that sex workers can mobilise against specific structural factors that marginalise them particularly (policies, structures and laws to deter sex work), which is not the case with general populations. Similarly, it is possible that mobilising a sub-set of a population is easier than mobilising entire communities. For the case of youth, hence, if they were discriminated against (as is the case of MSM in some contexts), this might foster a collective identity in the group, which would in turn facilitate tackling identifiable social determinants of health among this group.

Second, CMI seem more likely to generate favourable outcomes if accompanied by efforts for change at the structural level. For example, Kerrigan and colleagues’ study in the Dominican Republic provided evidence that CMI alone renders some positive outcomes, but when implemented alongside structural changes such as brothel policy of 100 % condom use its results were more effective [14]. Similarly, researchers of the MEMA kwa Vijana trial identified the low status of young people in the community as a barrier to attaining better results as well as females’ lower social status and financial reliance on males [75]. These factors, among other sociocultural issues identified by researchers, point to the need to work not only with the ‘target group’ but also with other community groups, in order to tackle structural barriers to CMI effectiveness.

Critique: Why are the Findings Inconclusive?

We suggest that the evidence is inconclusive not because CMI are ineffective, but instead due to problems with operationalization, evaluation and review methodologies. In other words, the full potential of CMI has rarely been evaluated. In what follows, we discuss problems in the literature, at the level of operationalization of CM, the attention to socio-political context, and the nature of review methodologies. While these problems afflict some parts of the literature, various authors have actively sought to address the problems appropriately. Thus, following each problem we also discuss ways of pre-empting or mitigating such problems.

First, inconclusive results may be related to the operationalization of CM. For complex interventions and trials in general there are a number of programme design issues that impinge on intervention impact, such as programme length, follow-up timespan, intervention exposure and adherence, as well as “underpowered” designs, as has been previously pointed out [33, 50, 60, 76]. In this review, we have identified three flaws in the operationalization which we discuss in turn: (i) understandings of CM remain underdeveloped, and often tokenistic; (ii) implementations of CMI are often characterised by inflexibility; and (iii) the evaluation of CMI tends to inadequately account for social impact.

The first point about operationalization concerns the degree to which CM interventions allow for genuine community ownership. In theory, the merit of CM lies in building sustainable community strengths and agency at the community level [77, 78]. In practice, however, the concept is often used to refer to static and tokenistic activities in which researchers gather “the community” and establish contact with relevant stakeholders. Despite our efforts to employ appropriate inclusion criteria, limited versions of CM were employed in several of our reviewed studies. This was particularly notable in interventions with youth and general communities. Articles describing the nature of CM in the reviewed studies included statements referring to CM as “community sensitisation…to inform the community about the study” and to obtain authorisation [79], activities “to reduce opposition” to the intervention programme [75], “the process of gaining community support for the study” [80], and undertakings to ascertain leaders’ “views and seek their support in encouraging community participation” [81]. In these instances, interventions draw on local knowledge and input to execute programmes planned by outsiders [82]. In such cases, at best, communities are “mobilised” first, to gain access to their networks and thus enable research execution and second, to participate in programme delivery [82]. They may not in fact be building and capitalising on the community connections that comprise the main rationale for CM.

Examples of projects that managed to operationalize CM in a way that fostered supportive community relations come from those targeting sex workers and groups most at risk. Overall, these interventions included activities that triggered active community engagement through de-stigmatising public events, fostering of within-community cohesion and alliances with external stakeholders. The Princesinha project in Brazil [68], for example, engaged sex workers as leaders of project activities and data collectors. Public exposure was raised through celebrating the eldest sex worker, carnival participation through a “prejudice-free” samba group carrying prevention posters [68]. In a similar attempt in Brazil, the Encontros project [83] included activities that allowed within-community dialogue around sex work, discrimination, human rights and HIV/STI prevention. They also organised “hot-pink” parties, cultural performances by sex workers at the city’s cultural centre, along with external partnerships with the community at large [83]. What these and other interventions [e.g. 72] have in common is the thoughtful implementation of activities that are inclusive of community members and build cohesive relationships among them, while fostering their self-presentation as an assertive ‘community’ in negotiations with stakeholders in the public sphere.

Stemming from this understanding of CM and in line with requirements of standardisation of intervention components in evaluation research, the second problem at the level of operationalization is inflexibility in the way the majority of the programmes included in our review responded to the needs of communities. A premise of CM is that interventions must be appropriate, and thus adapted to specific local contexts based on community ownership and leadership [2, 18]. However, when studies reported changes in the planned implementation and evaluation, this was presented as a remedial measure taken by researchers, which limits meaningful engagement of the target community and therefore ownership of the project’s objectives. For instance, the Manicaland project did not implement the income-generating intervention component originally planned because of country-wide economic decline during the trial [52]. While Stepping Stones programmers acknowledged that “development of interventions is an iterative process, and interventions are generally strengthened by being more extensively tested and adapted” [51], adaptations to the original intervention occurred before this trial was implemented and to fulfil research needs rather than community demands [51].

Among the studies included in this review, two interventions made explicit adaptations while implementing CM. Project Accept [84] made an explicit programmatic point of allowing “site-specific adaptations” to accommodate “site-specific sociocultural differences” in its varying settings. Researchers developed a thoughtful way of balancing consistency and flexibility while maintaining a “minimum level of comparability” [85]. Strategies used to enable consistency of themes across adaptations included engaging field staff in producing the adaptations, ensuring community acceptance, and using steering committee, ethical review boards and intervention subcommittees to approve and implement adaptations [85]. The Avahan intervention also documented the changes applied according to community demands during its implementations [86]. The remaining challenge, of course, is that such complexity, changes, and relative lack of control are at odds with the requirements of rigorous and internally-valid designs such as RCT.

The third problematic point regarding the current operationalization of CM concerns methodological issues in the measurement of impact, particularly social impact. The choice of impacts to measure, and of measurement tools, is often weak, particularly for social outcomes. There might be benefits gained by CMI participants that are not necessarily part of the programmes’ evaluated outcomes (e.g. health service use) or that are intangible (e.g. increased participation in groups outside the ‘target’ community). Among interventions with sex workers, some programmes [55, 59] limit the appraisal of social outcomes to one question per dimension (e.g. collective efficacy), restricting the power of such measurements. This indicates the need both to improve quantitative instruments, and to triangulate evidence from more open-ended data collection methods, to maximise learning from an intervention.

For example, some of the studies included in this review have used process evaluation to explain their quantitative effects [75, 87] to document the challenges of implementing RCT among deprived, rural groupings [81], and to report the most successful CM approaches to engage communities [88]. Process evaluation represents a viable option to gauge the social transformations triggered by CMI because it documents the context of the ‘black box’ that often seems to be present in ‘input–output’ models. In addition, it documents ‘achievements’ that are part of the intervention per se. This is the case because in many contexts the sheer implementation of the programme might be in fact contesting the status quo of its target population, which was the case of a number of studies in this review [67, 68], but that is often missed in quantitative evaluations such as those included here.

Second, many of the interventions failed to engage with the broader social and political context and power relations that structure health in very disadvantaged communities [2]. Contemporary understandings of CM emphasise that communities alone rarely have the power to make the social changes needed to sustain healthy behaviour, and hence, that alongside CM, efforts to engage powerful stakeholders and to move towards structural changes are also required [18, 27, 89]. In contrast to these understandings, in programmes involving youth and general communities, there was evidence of limited efforts to engage the broader community. Where efforts were made to engage groups beyond the target group, this often had the limited aim of enabling the diffusion of health-related knowledge, to parents or other groups [53, 79] rather than engaging them in transformative change.

Among our reviewed studies, it was notable that interventions with sex workers often took greater account of the socio-political context. In such studies, having a support network, altering community relationships and fostering collective action have the potential to bring much wider benefits and thus be valued in their own right, beyond their contribution specifically to HIV prevention. For instance, advocacy was conducted with the police, local government officials, community leaders, FSW’s partners and clients, and other gatekeepers [62, 66]. In this way, the ‘community’ that brings about the project is more inclusive than the interventions’ target community groups [23].

Third, reflecting on the very uneven nature of the findings, we suggest that the goal of providing an over-arching statement of ‘the evidence’ for CM may itself be misguided [90, 91]. Most obviously, we have noted that there is a different pattern of findings for sex workers and for youth and general communities. We have observed that in some studies, there appear to be impacts on condom use with some types of partners, but not others. The IMAGE study found impressive effects on intimate partner violence (and this is widely argued to be a likely contributor to HIV transmission), but no effects on HIV incidence, which by its nature is more difficult to assess. Based on earlier positive results from the Sonagachi Project [16, 92], replications were implemented in Brazil [67, 70] and India [65, 66] but to less positive effect. Furthermore, the Avahan intervention has disaggregated CM components and their impact on a host of measures of condom use in a variety of settings, finding some significant relationships at a fine-grained level, but not much consistency across results [57–59, 61, 62].

Such inconsistent findings make it appear unrealistic to expect a singular statement about whether CM ‘works’ or not. More nuanced statements, about the conditions under which CM is more likely to work might have greater potential (e.g. our review suggests that CM may be more likely to succeed if it is implemented in tandem with policy changes). However, it seems unlikely that a definitive set of decision rules to determine when CM should be attempted could be achieved. CM is, by its very nature, contextual and evolving. CM mobilises contextually-specific local networks, in locally-appropriate ways, and allows communities power to create and alter objectives. Thus, CM is not simply an intervention that is equivalent across sites, but takes different forms in different sites. Although the ‘evidence-based policy and practice’ paradigm prioritises controlled trials and systematic reviews of these, it may be that multi-faceted and context-specific CMI are more challenging to quantify, compare and appraise.

Implications

The above critical discussion has implications for future implementation and evaluation of CM. The first is the need for operationalization of CM informed by a committed understanding of social change. We are concerned that the evaluated CMI may not in fact be a good test of the effectiveness of CM, because the interventions do not always heed the transformative objectives behind CM, but treat it simply as an instrumental add-on to increase uptake, being inflexible to the contextual needs of the community participating in the intervention, and using simplistic measures of social outcomes. Part of the issue may be that the improvisational and responsive nature of genuine CM is not compatible with the methodological requirements of controlling variables and standardising intervention components. Another possibility is that the biomedical professionals who often lead such interventions are not equipped with the skills to facilitate an open-ended and complex social process of mobilisation [2, 93]. We propose that a clear understanding of CM, informed by a social scientific theory of change, and recognising the need for specific community development skills is needed. The more established our understanding of CM is, the less likely it will be that the concept is stripped-down and depoliticised when operationalized.

Second, our discussion of context and social groups points towards the need to work with communities to address the socio-political context and to build supportive partnerships with more powerful groups, rather than with community groups in isolation. An enabling policy environment (e.g. decriminalisation and de-stigmatisation of sex work and homosexuality, governmental policies for participatory community planning of interventions) is required for communities to address socio-political issues. The reviewed studies targeting sex workers illustrate that, when such an enabling environment is absent, advocacy may be needed as part of CMI in order to negotiate power relations.

Finally, our critique of the systematic review methodology suggests that judgements about the suitability of CM may need to be made on a more local basis, and informed by a wider set of evidence than that provided by systematic reviews and/or rigorous outcome evaluations. Contemporary work in the philosophy of science questions the desirability of conceptualising social interventions in terms of ‘replication’ across diverse contexts, arguing that “to draw causal inferences about a target population, which method is best depends case-by-case on what background knowledge we have” [94]. The implication here is that a systematic review of outcome evaluations is insufficient information on which to base the choice or design of a CM intervention. Such information needs to be combined with other sources, including a plausible theory of change and knowledge of the particular context into which the intervention is being introduced.

Conclusion

Taking the evidence at face value (irrespective of our critiques of the form of this evidence), it seems too early to decide whether CM works or not, especially considering the heterogeneity of interventions. At present, at least two RCT which explicitly include CM as a component are being conducted and awaiting biomedical results [95, 96]. They may offer further evidence of the contribution of these quantifying approaches to the planning, implementation and evaluation of CM as currently conceptualised. However, taking our critiques seriously, we suggest that the very aspiration to provide a single statement of ‘the evidence’ for diverse, evolving, and multifaceted CMI in complex settings may be misguided.

References

Vaughan C. “When the road is full of potholes, I wonder why they are bringing condoms?” Social spaces for understanding young Papua New Guineans’ health related knowledge and health-promotion action. AIDS Care. 2010;2(Suppl. 2):1644–51.

Campbell C. ‘Letting them die’ Why HIV/AIDS programmes fail. Oxford: James Currey; 2003.

Aveling EL. Making sense of ‘gender’: from global HIV/AIDS strategy to the local Cambodian ground. Health Place. 2012;18(3):461–7.

Schwartländer B, Stover J, Hallet T, et al. Towards and improved investment approach for an effective response to HIV/AIDS. Lancet. 2011;377:2031–41.

Lissouba P, Taljaard D, Rech D, et al. A model for the roll-out of comprehensive adult male circumcision services in African low-income settings of high HIV incidence: the ANRS 12126 Bophelo Pele Project. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000309.

Mahler HR, Kileo B, Curran K, et al. Voluntary medical male circumcision: matching demand and supply with quality and efficiency in a high-volume campaign in Iringa Region, Tanzania. PLoS Med. 2011;8(11):e1001131.

Coates TJ, Richter L, Caceres C. Behavioural strategies to reduce HIV transmission: how to make them work better. Lancet. 2008;372(9639):669–84.

Darrow WW, Montanea JE, Fernández PB, et al. Eliminating disparities in HIV disease: community mobilization to prevent HIV transmission among Black and Hispanic young adults in Broward County, Florida. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3; suppl 1):S1–108.

Auerbach JD, Parkhurst JO, Cáceres CF. Addressing social drivers of HIV/AIDS for the long-term response: conceptual and methodological considerations. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(sup3):S293–309.

Blankenship KM, Friedman SR, Dworkin S, Mantell JE. Structural interventions: concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. J Urban Health. 2006;83(1):59–72.

Blankenship KM, Biradavolu MR, Jena A, George A. Challenging the stigmatization of female sex workers through a community-led structural intervention: learning from a case study of a female sex worker intervention in Andhra Pradesh, India. AIDS Care. 2010;22(S2):1629–36.

Shahmanesh M, Patel V, Mabey D, et al. Effectiveness of interventions for the prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in female sex workers in resource poor setting: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(5):659–79.

Busza J, Baker S. Protection and participation: an interactive programme introducing the female condom to migrant sex workers in Cambodia. AIDS Care. 2004;16(4):507–18.

Kerrigan D, Moreno L, Rosario S, et al. Environmental-structural interventions to reduce HIV/STI risk among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(1):120–5.

Sweat M, Morin S, Calentano D, et al. Community-based interventions to increase HIV testing and case detection in people aged 16–32 years in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Thailand (NIMH Project Accept, HPTN 043): a randomised study. Lancet. 2011;11:525–32.

Jana S, Basu I, Rotheram-Borus MJ, et al. The Sonagachi project: a sustainable community intervention program. AIDS Educ Prev. 2004;16(5):405–14.

Lippman SA, Maman S, MacPhail C, et al. Conceptualizing community mobilization for HIV prevention: implications for HIV prevention programming in the African context. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e78208.

Campbell C, Cornish F. Towards a “fourth generation” of approaches to HIV/AIDS management: creating contexts for effective community mobilisation. AIDS Care. 2010;22(Suppl. 2):1569–79.

Obregón R, Waisbord S. The complexity of social mobilization in health communication: top-down and bottom-up experiences in polio eradication. J Health Commun. 2010;15(S1):25–47.

Campbell C, Scott K, Nhamo M, et al. Social capital and HIV competent communities: the role of community groups in managing HIV/AIDS in rural Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2013;25(S1):114–22.

Skovdal M, Magutshwa-Zitha S, Campbell C, et al. Community groups as ‘critical enablers’ of the HIV response in Zimbabwe. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):195.

Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Sherr L, et al. Grassroots community organizations’ contribution to the scale-up of HIV testing and counselling services in Zimbabwe. AIDS. 2013;27(10):1657.

Cornish F, Ghosh R. The necessary contradictions of ‘community-led’ health promotion: a case study of HIV prevention in an Indian red light district. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(2):496–507.

Evans C, Lambert H. Implementing community interventions for HIV prevention: insights from project ethnography. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:467–78.

Hatcher A, de Wet J, Bonell CP, et al. Promoting critical consciousness and social mobilization in HIV/AIDS programmes: lessons and curricular tools from a South African intervention. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(3):542–55.

Campbell C, Cornish F. How can community health programmes build enabling environments for transformative communication? Experiences from India and South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(4):847–57.

Cornish F, Campbell C. The social context of community mobilization: foundations for success or failure. AIDS Care. 2010;22(Suppl 2):1670–8.

Campbell C, Nair Y, Maimane S. Building contexts that support effective community responses to HIV/AIDS: a South African case study. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;39:347–63.

Cornish F, Shukla A, Banerji R. Persuading, protesting and exchanging favours: strategies used by Indian sex workers to win local support for their HIV prevention programmes. AIDS Care. 2010;22(Suppl. 2):1670–8.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337(sep29):a1655.

Victoria CG, Habicht JP, Bryce J. Evidence-based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):400–5.

Bonell C, Hargreaves J, Strange V, et al. Should structural interventions be evaluated using RCTs? The case of HIV prevention. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1135–42.

Ross DA. Behavioural interventions to reduce HIV risk: what works? AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl. 4):S4–14.

Gupta GR, Parkhurst JO, Ogden JA, et al. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372(9640):764–75.

World Bank. Country and lending groups. http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 22 Oct 2012.

Gallo MF, Behets FM, Steiner MJ, et al. Validity of self-reported ‘safe sex’ among female sex workers in Mombasa, Kenya—PSA analysis. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(1):33–8.

Minnis AM, van der Straten A, Gerdts C, et al. A comparison of four condom-use measures in predicting pregnancy, cervical STI and HIV incidence among Zimbabwean women. Sex Trans Inf. 2010;86(3):231–5.

Rose E, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. The validity of teens’ and young adults’ self-reported condom use. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(1):61–4.

Schensul SL, Saggurti N, Burleson JA, et al. Community-level HIV/STI interventions and their impact on alcohol use in urban poor populations in India. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:S158–67.

Arora P, Nagelkerke N, Sgaier SK, et al. HIV, HSV-2 and syphilis among married couples in India: patterns of discordance and concordance. Sex Trans Inf. 2011;87(6):516–20.

Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J. An introduction to systematic reviews. London: Sage; 2012.

Campbell C. Health psychology and community action. In: Murray M, editor. Critical health psychology. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2004.

Cooke R, Sheeran P. Moderation of cognition-intention and cognition-behaviour relations: a meta-analysis of properties of variables from the theory of planned behaviour. Br J Soc Psychol. 2004;43(2):159–86.

Sheeran P, Orbell S. Do intentions predict condom use? Metaanalysis and examination of six moderator variables. Br J Soc Psychol. 2011;37(2):231–50.

Thomas H. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Effective Public Health Practice Project. McMaster University, Toronto. http://www.ephpp.ca/Tools.html. Accessed 6 Sept 2012.

Jackson N, Waters E. Criteria for the systematic review of health promotion and public health interventions. Health Promot Int. 2005;20(4):367–74.

Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, et al. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–84.

Coates T, Eshleman S, Chariyalertsak S, et al. Findings on estimates of community-level HIV incidence in NIMH Project Accept (HPTN 043). Paper presented at the 20th conference on retroviruses and opportunistic infections. 2013 March 3–6; Atlanta.

Cowan FM, Pascoe SJS, Langhaug LF, et al. The Regai Dzive Shiri project: results of a randomized trial of an HIV prevention intervention for youth. AIDS. 2010;24(16):2541–52.

Doyle AM, Ross DA, Maganja K, et al. Long-term biological and behavioural impact of an adolescent sexual health intervention in Tanzania: follow up survey of the community-based MEMA kwa Vijana trial. PLOS Med. 2010;7(6):e1000287.

Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, et al. Impact of Stepping Stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 2008;337:a506.

Gregson S, Adamson S, Papaya S, et al. Impact and process evaluation of integrated community and clinic-based HIV-1 control: a cluster-randomised trial in Eastern Zimbabwe. PLOS Med. 2007;4(3):0545–55.

Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, et al. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1973–83.

Kamali A, Quigley M, Nakiyingi J, et al. Syndromic management of sexually-transmitted infections and behaviour change interventions on transmission of HIV-1 in rural Uganda: a community randomised trial. Lancet. 2003;361:645–62.

Blankenship KM, West BS, Kershaw TS, et al. Power, community mobilization, and condom use practices among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh. India. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl. 5):S109–16.

Erausquin JT, Biradavolu M, Reed E, et al. Trends in condom use among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India: the impact of a community mobilisation intervention. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(Suppl. 2):ii49–54.

Saggurti N, Mishra RM, Proddutoor L, et al. Community collectivization and its association with consistent condom use and STI treatment-seeking behaviors among female sex workers and high-risk men who have sex with men/transgenders in Andhra Pradesh, India. AIDS Care. 2013;25(sup1):S55–66.

Blanchard AK, Mohan HL, Shahmanesh M, et al. Community mobilization, empowerment and HIV prevention among female sex workers in south India. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):234.

Guha M, Baschieri A, Bharat S, et al. Risk reduction and perceived collective efficacy and community support among female sex workers in Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra, India: the importance of context. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(Suppl 2):ii55–61.

Ng M, Gakidou E, Levin-Rector A, et al. Assessment of population-level effect of Avahan, an HIV-prevention initiative in India. Lancet. 2011;378:1643–52.

Ramesh BM, Beattie TSH, Shajy I, et al. Changes in risk behaviours and prevalence of sexually transmitted infections following HIV preventive interventions among female sex workers in five districts in Karnataka state, south India. Sex Trans Inf. 2010;86(Suppl. 1):i17–24.

Reza-Paul S, Beattie T, Syed HUR, et al. Declines in risk behaviour and sexually transmitted infection prevalence following a community-led HIV preventive intervention in Mysore, India. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl. 5):S91–100.

Gutierrez JP, McPherson S, Fakoya A, et al. Community-based prevention leads to an increase in condom use and a reduction in sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among men who have sex with men (MSM) and female sex workers (FSW): the Frontiers Prevention Project (FPP) evaluation results. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):497.

Parimi P, Mishra RM, Tucker S, et al. Mobilising community collectivisation among female sex workers to promote STI service utilisation from the government healthcare system in Andhra Pradesh, India. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(Suppl 2):ii62–8.

Swendeman D, Basu I, Das S, et al. Empowering sex workers in India to reduce vulnerability to HIV and sexually transmitted diseases. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:1157–66.

Basu I, Jana S, Rotheram-Borus MJ, et al. HIV Prevention among sex workers in India. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36(3):845–52.

Lippman SA, Chinaglia M, Donini AA, et al. Findings from Encontros: a multilevel STI/HIV intervention to increase condom use, reduce STI and change the social environment among sex workers in Brazil. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(3):209–16.

Benzaken AS, Galbán Garcia E, Sardinha JCG, et al. Community-based intervention to control STD/AIDS in the Amazon region, Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2007;41:118–26.

Gutiérrez JP, Atienzo EE, Bertozzi SM, McPherson S. Effects of the Frontiers Prevention Project in Ecuador on sexual behaviours and sexually transmitted infections amongst men who have sex with men and female sex workers: challenges on evaluating complex interventions. J Dev Effect. 2013;5(2):158–77.

Kerrigan D, Telles P, Torres H, et al. Community development and HIV/SIT-related vulnerability among female sex workers in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(1):137–45.

Williams BG, Taljaard D, Campbell CM, et al. Changing patterns of knowledge, reported behaviour and sexually transmitted infections in a South African gold mining community. AIDS. 2003;17(14):2099–107.

Gao MY, Wang S. Participatory communication and HIV/AIDS prevention in a Chinese marginalized (MSM) population. AIDS Care. 2007;19(6):799–810.

Schensul SL, Saggurti N, Singh R, et al. Multilevel perspectives on community intervention: an example from an Indo-US prevention project in Mumbai, India. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;43:277–91.

Ghose T, Swendeman D, George S, Chowdhury D. Mobilizing collective identity to reduce HIV risk among sex workers in Sonagachi, India: the boundaries, consciousness, negotiation framework. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(2):311–20.

Wight DE, Plummer ML, Ross DA. The need to promote behaviour change at the cultural level: one factor explaining the limited impact of the MEMA kwa Vijana adolescent sexual health intervention in rural Tanzania. A process evaluation. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):788.

Padian N, McCoy S, Balkus JE, et al. Weighting the gold in the gold standard: challenges in HIV prevention research. AIDS. 2010;24:621–35.

Rosato M, Laverack G, Grabman LH, et al. Community participation: lessons from maternal, newborn and child health. Lancet. 2008;372:962–71.

Trickett EJ. Context, culture, and collaboration in AIDS interventions: ecological ideas for enhancing community impact. J Prim Prev. 2002;23(2):157–74.

Cowan FM, Pascoe SJ, Langhaug LF, et al. The Regai Dzive Shiri Project: a cluster randomised controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of a multi-component community-based HIV prevention intervention for rural youth in Zimbabwe–study design and baseline results. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(10):1235–44.

Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, et al. A cluster randomized-controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of Stepping Stones in preventing HIV infections and promoting safer sexual behaviour amongst youth in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa: trial design, methods and baseline findings. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11(1):3–16.

Mitchell K, Nakamanya S, Kamali A, et al. Balancing rigour and acceptability: the use of HIV incidence to evaluate a community-based randomised trial in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(7):1081–91.

Trickett EJ. Community-based participatory research as worldview or instrumental strategy: is it lost in translation (al) research? Am J Public Health. 2011;101(8):1353–5.

Lippman SA, Donini A, Díaz J, et al. Social-environmental factors and protective sexual behavior among sex workers: the Encontros intervention in Brazil. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S216–23.

Khumalo-Sakutukwa G, Morin SF, Fritz K, et al. Project Accept (HPTN 043): a community-based intervention to reduce HIV incidence in populations at risk for HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa and Thailand. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(4):422–31.

Kevany S, Khumalo-Sakutukwa G, Murima O, et al. Health diplomacy the adaptation of global health interventions to local needs in sub-Saharan Africa and Thailand: evaluating findings from Project Accept (HPTN 043). BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):459.

Wheeler T, Kiran U, Dallabetta G, et al. Learning about scale, measurement and community mobilisation: reflections on the implementation of the Avahan HIV/AIDS initiative in India. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(Suppl. 2):ii16–25.

Hargreaves J, Hatcher A, Strange V, et al. Process evaluation of the Intervention with Microfinance for AIDS and Gender Equity (IMAGE) in rural South Africa. Health Educ Res. 2010;25(1):27–40.

Tedrow VA, Zelaya CE, Kennedy CE, et al. No “Magic Bullet”: exploring community mobilization strategies used in a multi-site community based randomized controlled trial: Project Accept (HPTN 043). AIDS Behav. 2012;16(5):1217–26.

Cornish F, Dashtipour P, Mannell J, Montenegro C. Towards a theory of change: Report on an interview study of the International HIV/AIDS Alliance. London: Health, Community & Development Research Group, LSE; 2012.

Shepperd S, Lewin S, Straus S, et al. Can we systematically review studies that evaluate complex interventions? PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000086.

Seckinelgin H. What is the evidence that there is no evidence? The link between conflict, displacement and HIV infections. Eur J Dev Res. 2010;22:363–81.

Jana S, Singh S. Beyond medical model of STD intervention—lessons from Sonagachi. Indian J Public Health. 1995;39:125–31.

Cornish F, Campbell C. The social conditions for successful peer education: a comparison of two HIV prevention programs run by sex workers in India and South Africa. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;44(1–2):123–35.

Cartwright N. Are RCTs the gold standard? Biosocieties. 2007;2(1):11–20.

Kawichai S, Celentano D, Srithanaviboonchai K, et al. NIMH Project Accept (HPTN 043) HIV/AIDS community mobilization (CM) to promote mobile HIV voluntary counseling and testing (MVCT) in rural communities in Northern Thailand: modifications by experience. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(5):1227–37.

Abramsky T, Devries K, Kiss L, et al. A community mobilisation intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV/AIDS risk in Kampala, Uganda (the SASA! Study): study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13(1):96.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the International HIV/AIDS Alliance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cornish, F., Priego-Hernandez, J., Campbell, C. et al. The impact of Community Mobilisation on HIV Prevention in Middle and Low Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Critique. AIDS Behav 18, 2110–2134 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0748-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0748-5