Abstract

Many questionnaires have been developed to measure physical activity (PA), but an overview of the measurement properties of PA questionnaires is lacking. A summary of this information is useful for choosing the best questionnaire available. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate and compare measurement properties of self-administered questionnaires assessing PA in adults. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and SportDiscus®, using ‘exercise’, ‘physical activity’, ‘motor activity’ and ‘questionnaire’ as keywords. We included studies that evaluated the measurement properties of self-report questionnaires assessing PA. Article selection, data extraction and quality assessment were performed by two independent reviewers. The quality and results of the studies were evaluated using the Quality Assessment of Physical Activity Questionnaires (QAPAQ) checklist. Construct validity, reliability and responsiveness were rated as positive, negative or indeterminate, depending on the methods and results. We included 85 (versions of) questionnaires. Overall, the quality of the studies assessing measurement properties of PA questionnaires was rather poor. Information on content validity was mostly lacking. Construct validity was assessed in 76 of the questionnaires, mostly by correlations with accelerometer data, maximal oxygen uptake or activity diaries. Fifty-one questionnaires were tested for reliability. Only a few questionnaires had sufficient construct validity and reliability, but these need to be further validated. Responsiveness was studied for only two questionnaires and was poor. There is a clear lack of standardization of PA questionnaires, resulting in many variations of questionnaires. No questionnaire or type of questionnaire for assessing PA was superior and therefore could not be strongly recommended above others. In the future, more attention should be paid to the methodology of studies assessing measurement properties of PA questionnaires and the quality of reporting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Adequately measuring physical activity (PA) is important for determining trends in PA levels over time, for evaluation of the effect of PA interventions and for determining health benefits of PA. Poor measurement of PA may hinder detection of important associations or effects.[1] Many questionnaires have been developed to measure PA. Some questionnaires were developed specifically for a certain subgroup or setting, others because researchers were not aware of existing questionnaires or because they were not satisfied with available questionnaires. Often researchers needed to translate and/or adapt existing questionnaires to other target groups. This has led to a large number of (versions of) questionnaires available, which makes it difficult to choose the most suitable instrument. Furthermore, the use of different instruments in different studies and surveys makes comparison of PA levels across countries or studies difficult.

To our knowledge, an overview of the measurement properties of PA questionnaires is lacking. A summary of these findings might be helpful for choosing the best questionnaire available for a specific purpose. Furthermore, a critical assessment of the methodological quality of the studies assessing the measurement properties of PA questionnaires is lacking, while the methodological quality of these studies might be variable. If the methodological quality of a study is poor, the results and conclusions can be seriously biased. For example, wrong conclusions can be drawn from a validation study if no adequate comparison instrument was used. It is therefore important to assess the methodological quality of a study to be confident that the design, conduct, analysis and interpretation of the study is adequate, and to inform about possible bias that might have influenced the results.

In this article, we aim to evaluate and compare the measurement properties of all available self-administered questionnaires measuring PA in adults, using a systematic approach for the literature search, data extraction and assessment of the quality of the studies. This article is one of a series of four articles on measurement properties of PA questionnaires published in Sports Medicine.

1. Methods

1.1 Literature Search

Literature searches were performed in PubMed, EMBASE using ‘EMBASE only’, and in SportDiscus® (complete databases until May 2009) on the topic of self-report questionnaires of PA. Additional papers were identified by manually searching references of the retrieved papers and the authors’ own literature databases.

The full search strategy in PubMed was as follows: (exercise[MeSH] OR ‘physical activity’[tiab] OR motor activity[MeSH]) AND (questionnaire[MeSH] OR questionnaire*[tiab]), and limited to humans. In EMBASE and SportDiscus®, ‘physical activity’ and ‘questionnaire’ were used as free text words and in EMBASE this was complemented with the EMTREE term ‘exercise’.

1.2 Eligibility Criteria

We used the following inclusion criteria:

1. The aim of the study should be to develop or evaluate the measurement properties – i.e. content validity, construct validity, reliability or responsiveness – of a self-report questionnaire.

2. The aim of the questionnaire should be to measure PA, which was defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure above resting level.[2] PA in daily life can be categorized into occupational, sports, conditioning, household or other activities. Questionnaires were included regardless of the time frame; thus, questionnaires measuring lifetime PA or historical activity were also included.

3. The questionnaire could be used to measure PA in adults in the general population, and was not developed or evaluated in a specific population, such as patients or pregnant or obese participants.

4. The study sample should have a mean age between 18 and 55 years.

5. The article should have been published in the English language.

6. Information on (at least one of) the measurement properties of the self-report questionnaire should be provided. We included information on measurement properties only if it was intentionally collected or calculated to assess the measurement properties of the particular self-report questionnaire. If, for example, correlations between a self-report questionnaire and an accelerometer were presented to assess the validity of the accelerometer (while the self-report questionnaire was used as a gold standard) or if correlations between different PA questionnaires were calculated without one questionnaire considered as the standard, these data were not included in this review.

7. We excluded PA interviews or diaries. We also excluded studies that evaluated the measurement properties of a self-report questionnaire administered in an interview form. Finally, questionnaires measuring physical functioning (e.g. the degree to which one is limited in carrying out activities) and questionnaires asking about sweating in a single question were excluded.

1.3 Selection of Papers

Abstract selection, selection of full-text articles, data extraction and quality assessment were performed by two independent reviewers. Disagreements were discussed and resolved. We retrieved the full-text paper of all abstracts that fulfilled the inclusion criteria and of abstracts that did not contain measurement properties, but in which indications were found that these properties were presented in the full-text paper.

1.4 Data Extraction

We extracted a description of the self-report questionnaires from the included papers, using a standardized data extraction form. Data extracted included (i) the target population for which the questionnaire was developed; (ii) the dimension(s) of PA that the questionnaire intends to measure (e.g. habitual PA); (iii) the parameters of PA that the questionnaire is measuring (i.e. frequency, duration and intensity or activities); (iv) the setting in which PA is being measured (i.e. sport, recreational, transport, occupational/school activities, household activities [including gardening], other); (v) the number of questions; (vi) the recall period that the questions refer to; and (vii) the type and number of scores that were calculated (e.g. total energy expenditure or minutes of activity per day).

1.5 Quality Assessment of the Studies on Measurement Properties

To assess the methodological quality and results of the studies on measurement properties, we used the QAPAQ checklist (see table I for acronym definitions). We developed this checklist specifically for PA questionnaires, based on two recently developed checklists to evaluate the measurement properties of patient-reported outcomes COSMIN[8] and self-report health status questionnaires.[33] The QAPAQ is described elsewhere.[29] We extracted and rated the methods and results of all evaluated measurement properties (see sections 1.7–1.9).

1.6 Content Validity

No criterion exists to rate whether the content of a questionnaire is relevant and comprehensive for measuring PA. Therefore, we formed our own opinion on content validity. Questionnaires should measure at least duration and frequency of PA, and if the intention was to measure total PA, the questionnaire should cover activities in all settings (work, home, transport, recreation, sport).

1.7 Construct Validity

The more similar the constructs that are being compared, the more evidence is provided for validity. Comparison with objective measures of PA (doubly labelled water, accelerometers, pedometers) was considered the best level of evidence (Level 1 or 2, depending on the use of the objective data). We considered constructs not really measuring current PA (maximal oxygen uptake [V̇O2max], body mass index [BMI], etc.) or another questionnaire, a diary or interview as less adequate comparison measures (Level 3). Depending on the strength of the hypothesized association with the comparison measure, different correlations were considered to be adequate (table II).

A positive score was given if the study population consisted of ≥50 participants and the correlation was above the specified cut-off point. If the correlation was below the specified cut-off point, a negative score was given. If the sample size was <50 participants, the score was indeterminate (?).

1.8 Reliability

The time interval between the test and retest must have been described and short enough to ensure that subjects had not changed their PA levels, but long enough to prevent recall. The most optimal time interval depends on the construct to be measured and the recall period of the questionnaire. For measuring PA during the past or usual week or in the past year, a time interval of 1 day to 3 months was considered appropriate. For measuring lifetime PA, a time interval from 1 day to 12 months was considered appropriate.

For reliability, three levels of evidence were formulated:

-

Level 1: an adequate time interval between test and retest and an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), Kappa or Concordance.

-

Level 2: an inadequate time interval between test and retest and an ICC, Kappa or Concordance; or an adequate time interval between test and retest and a Pearson/Spearman correlation.

-

Level 3: an inadequate time interval between test and retest and Pearson/Spearman correlation.

An ICC >0.70 was considered acceptable.[34] The use of Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients was considered inadequate, because it neglects systematic errors.[35] However, Pearson/Spearman correlations >0.80 would probably result in ICCs >0.70 and were therefore also rated positively, but on a second level of evidence. Pearson or Spearman correlations <0.80 were rated negatively.

A positive score was given if the study population consisted of ≥50 participants and the ICC, Kappa, Concordance or Pearson/Spearman correlation was above the specified cut-off point. If the correlation was below the specified cut-off point, a negative score was given. If the sample size was <50 participants, the score was rated as indeterminate (?).

1.9 Responsiveness

Responsiveness is the ability of an instrument to detect change over time in the construct to be measured.[36] It should be considered an aspect of validity in a longitudinal setting. Responsiveness was assessed by comparing changes in the PA questionnaire with changes in other instruments that measure closely related constructs. The same approach as for assessing validity was applied, except that change scores were being compared instead of absolute scores. Depending on the strength of the hypothesized association, different correlations were considered to be adequate.

2. Results

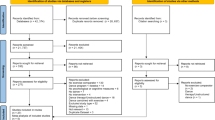

The search resulted in 21 891 hits, of which 260 abstracts were selected. Of the full-text articles with relevant titles and/or abstracts, 166 were excluded. Most of the papers were excluded because the questionnaire was administered in an interview or because no measurement properties of the questionnaire were assessed. Finally, 94 papers on 85 (versions of) questionnaires were included in the review (figure 1). Descriptive information on the questionnaires included in the review is provided in table III.

2.1 Quality of the Studies

Construct validity was assessed for 77 questionnaires in 85 studies. Of these 77 questionnaires, 16 were validated at Level 1 and an additional 22 questionnaires at Level 2. Objective comparison measures were often V̇O2max (n = 40), accelerometers (n = 41), heart rate monitor (n = 5), doubly labelled water (n = 7) or pedometer (n = 6) [table IV]. Two of the three questionnaires specifically designed to measure walking were validated against pedometers (Level 1). Surprisingly, appropriate cut-off points for analysing accelerometer data were often not used when assessing time spent in moderate to vigorous PA, but instead total counts were used, which does not discriminate between light, moderate or vigorous PA.

Reliability was assessed for 51 (versions of) questionnaires in 49 studies. Only 15 questionnaires were reliability-tested at Level 1 and an additional 36 questionnaires at Level 2 (table V). The most frequently occurring methodological shortcoming was that Pearson correlations instead of ICCs or Kappas were calculated. Another frequently occurring methodological shortcoming was an inadequate time interval between the test and retest.

Responsiveness was assessed for only two (versions of) questionnaires, and the quality of these studies was rated as Level 3.

2.2 Qualitative Attributes of the Questionnaires

In the study by Altschuler et al.,[7] it was tested whether respondents interpreted the LACE PA questionnaire and the CMH questionnaire as intended. In cognitive interviews, respondents described their thought processes while completing these two questionnaires. It was demonstrated that the term ‘intensity’ was frequently interpreted as emotional or psychological intensity rather than physical effort. In addition, it was found that respondents often counted the same activity more than once, overestimated occupational PA and mistook a list of examples for a definitive list.

We did not find studies in which the content validity of a PA questionnaire was assessed. However, we formed our own opinion on the content of the questionnaires.

Of the 85 (versions of) questionnaires included in this review, 23 had sufficient content validity: i.e. they covered all relevant settings of PA (e.g. for total PA all five settings; and for occupational PA only transport and work) and measured duration and frequency (Bharati,[45] EPIC original Questionnaire (Q),[10] EPAQ2,[9] Harvard/College Alumnus Q,[3,51] the long version of the IPAQ,[14] the adapted IPAQ,[54] Kaiser PA Survey,[56] LACE PA Q,[7] Minnesota LTPA Q,[61] Mail Survey of PA,[62] Norman Q,[70] NZPAQ-SF,[21] One-week recall Q,[71] PAFQ,[22] PA History Q,[72] PYTPAQ,[26] Singh Q,[77,78] SQUASH,[32] Historical RWJ questionnaire,[30] NPAQ,[20] Health Insurance Plan of NY,[3] TOQ[31,89] and London PA Q[88]).

2.3 Validation Results

Only the 48 studies that assessed construct validity at Level 1 or 2 are discussed below. Construct validity was assessed by validation against doubly labelled water for seven questionnaires.[16,21,40,81,104,105] In all these studies, the correlation of total energy expenditure assessed with the questionnaire and with doubly labelled water was lower than our criterion of 0.70, with Pearson correlations ranging between 0.31 and 0.58 (table IV).

In 41 studies, construct validity was assessed by validation against accelerometers (table IV). For only one questionnaire, validated in a study with >50 participants, the correlation between accelerometer data and total PA was >0.50 (Suzuki Q[81]).

In an attempt to find out which type of questionnaire performed best, we averaged the correlations found in the 41 studies using accelerometers as the comparison measure. It was clear that correlations differed slightly between vigorous and moderate activity, with higher correlations for vigorous activity (r = 0.32 vs 0.22). Also, a higher correlation was found for questionnaires asking about the past week, instead of a usual week/usual PA/current PA or about the past year (r = 0.41 vs 0.26 and 0.30, respectively).

Two questionnaires designed for measuring walking were validated against pedometers (Level 1). One scored negative[85] and the other was rated as indeterminate because of a statistical analysis that could not be interpreted.[84] The reliability of 15 versions of PA questionnaires was assessed at Level 1 (table V), and only five showed positive results: the self-administered, short version of the IPAQ on PA in the past 7 days (S7S),[93] the Modified HLAQ,[11,102] the NPAQ[20] and the Bone Loading History Q[86] scored positive on all aspects, and the Kaiser PA Survey[56] scored positive on all aspects, except ‘care giving’. The other questionnaires showed mixed results or scored negative on most aspects, or scored indeterminate because of a small sample size.

In addition to the 15 questionnaires for which evidence on Level 1 was available, Level 2 evidence was found for another 36 (versions of) questionnaires. For only six questionnaires, a positive score on Level 2 was given (Modified Baecke [(ARIC) Baecke],[4] Health Insurance Plan of NY Q,[3,31] Lipid Res Clin Q,[3,59] Minnesota LTPA Q,[3] the Minnesota Heart Health Program Q,[3] and the Minnesota Heart Health Program Occupational Q[31]). The other questionnaires showed mixed results or scored negative on most aspects, or scored indeterminate because of a small sample size.

When averaging the results of the reliability studies, no clear differences were found between questionnaires with different recall periods, between different time intervals between test and retest or between sexes. The only difference found was that, on average, the reliability for vigorous activity was higher than for moderate activity.

The responsiveness of a questionnaire was assessed in only two studies,[38,54] and seemed to be poor. The correlation between changes in self-reported PA and changes in supervised activity in a training programme was -0.07 for total energy expenditure and 0.01 for vigorous activity.[38] The correlation of change in PA assessed with an adapted version of the long form of the IPAQ with change in V̇O2max was 0.20 for men and 0.12 for women.[54]

3. Discussion

Although more than 90 papers have been published on the validity or reliability of PA questionnaires, this is the first systematic review of studies assessing the measurement properties of PA questionnaires, in which the results as well as the methodological quality of the individual studies have been taken into account. Our results indicate that the overall methodological quality of the studies could be much improved. Most common flaws were small sample size and inadequate analyses, and for construct validity, comparison measures that were not measuring the same construct.

An important finding of our review was the poor reporting of methods and results of the studies. It was often unclear what dimension of PA the questionnaire was supposed to measure. This made assessing content validity sometimes impossible. Furthermore, it was extremely difficult, if not impossible, to assess whether the same or slightly modified versions of questionnaires were used in some studies, and it was not always clear whether the data were derived from a self-report questionnaire or whether the questionnaire was part of an interview.

For assessing construct validity, it is important to formulate specific hypotheses in advance about expected correlations between the questionnaire under study and other measures. However, almost none of the studies had formulated such hypotheses. To be able to provide levels of evidence we formulated hypotheses regarding the strength of the association between comparison instruments. This methodology is not new, and the idea behind it is that, in retrospect, it is always easy and tempting to come up with explanations for the findings and conclude that the questionnaire is valid. In fact, most studies in our review concluded that the questionnaire under study was valid. However, when we applied our criteria we found that these conclusions were overly optimistic in almost all cases.

Reliability was also often poorly assessed. Many studies used large time intervals between the test and retest, and in most studies Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated instead of ICCs or Kappas. This is partly because we included studies performed many years ago, when Pearson correlation was still an accepted method, but nowadays there is a consensus that calculating ICCs or Kappas is the preferred method for assessing reliability.

Only two studies evaluated responsiveness, i.e. the ability of a questionnaire to detect change in PA over time. This is amazing, given the importance of responsiveness of a questionnaire when used in PA intervention studies. If a questionnaire has poor responsiveness, treatment effects cannot be detected, or only with large sample sizes. For some questionnaires, the majority of the population scored the highest or lowest possible score (e.g. with the modified CHAMPS[6]). When this happens, there is little opportunity for change, leading to low responsiveness. Although the methodology of assessing responsiveness tends to be less well understood, there is a consensus that responsiveness should be considered an aspect of validity, in a longitudinal context.[106] While construct validity is about the validity of a single score, responsiveness is about the validity of a change score. This means that similar methods can be applied as for assessing validity to assess the validity of changes in PA scores over time, i.e. stating a priori hypotheses.

We found that correlations between PA questionnaire data and accelerometer data were slightly higher in questionnaires asking about the previous week compared with those asking about a usual week. Often, accelerometers were worn in the week that was captured by the questionnaire. It might be that this explains why higher correlations were found for these questionnaires compared with those that asked about a usual week or usual PA. So, whether questionnaires asking about the previous week are really better in assessing PA, or that this is a consequence of the testing procedures, needs to be determined.

3.1 Limitations of this Review

As with any other systematic review, it is possible we missed some relevant papers with our literature search. We only used the search terms ‘questionnaire’, ‘physical activity’, ‘exercise’ and ‘motor activity’ and did not include alternative wordings, such as ‘survey’. However, after checking all references of relevant papers retrieved in our search, it proved that very few papers were missed.

Because of an overwhelming amount of data available, we had to be selective in what to present in this review. First of all, we chose to limit the review to self-administered questionnaires, realizing that some questionnaires have been used in other forms as well, such as interview-administered. We realized that with this restriction we have ignored some studies on questionnaires that can be either self-administered or used as an interview. The measurement properties of these questionnaires may be different in these two applications. Therefore, by restricting the review to one form of administration, the studies were more homogeneous and we felt better comparisons across questionnaires could be made, without allowing for the type of administration as well. Further, when assessing validity, only correlations with accelerometer data, V̇O2max, BMI and percentage body fat were extracted from the papers, because we felt that, although these are different constructs, these comparison measures were most closely related to the construct being measured in the questionnaires. We have ignored correlations with, for example, cholesterol or blood pressure in these comparisons because only a limited correlation with PA can be expected. Lastly, not all scores resulting from the questionnaires could be presented. We often restricted the information to the overall or total PA scores. Data were presented for men and women separately when relevant (i.e. in case of sex differences).

Interpretation of the results was difficult for some studies, mostly due to poor reporting. Although two reviewers independently extracted data from the papers, interpretation may have been incorrect in some cases. Given the number of studies included in the review, and the number of studies conducted a long time ago, we chose not to contact the authors of the original studies.

Many of the choices for scoring the quality of the studies have been made without a very strong basis on theory or evidence, simply because there is not much available to base these choices on. Others might have chosen different cut-off points for scoring negative or positive on validity or reliability. The same is true for the decision on what is a sufficient sample size and what is the appropriate time interval between test-retest. However, readers can decide according to their own insights and draw their own conclusions from the data provided in the tables.

3.2 Recommendations for Choosing a Questionnaire

Current US recommendations state that every adult should participate 2.5 hours a week in moderate intensity or 75 minutes a week in vigorous intensity aerobic PA or in an equivalent combination of moderate and vigorous intensity activity. Aerobic activity should be performed in episodes of at least 10 minutes, preferably spread throughout the week. Based on these recommendations, questionnaires for measuring total PA should at least measure duration and frequency, and measure PA in all settings (work, home, transport, recreation, sport) to have sufficient content validity. Especially older questionnaires, such as the Baecke questionnaire,[41] do not fulfil this criterion, because insight into what PA for health should entail has changed over time.

Of course, some researchers will need a PA questionnaire not only for measuring total PA but also for different purposes, and different aspects of PA might be relevant for their study. For instance, when looking at bone health, energy expended in cycling or swimming might be less important, but carrying loads would be of interest. So there will not be one questionnaire suitable for all purposes or target groups. The choice for a certain questionnaire should therefore always start with defining the purpose of the study and the PA measurement, after which the content validity of a possible questionnaire should be judged. Only then do construct validity and reliability need to be considered.

In this review, the content of 23 questionnaires was deemed appropriate for the dimension of PA it was intended to measure (Bharati,[45] EPIC original Q,[10] EPAQ2,[9] Harvard/College Alumnus Q,[3,51] the long version of the IPAQ,[14] the adapted IPAQ,[54] Kaiser PA Survey,[56] LACE PA Q,[7] LTPA Q,[61] Mail Survey of PA,[62] Norman Q,[70] NZPAQ-SF,[21] One-week recall Q,[71] PAFQ,[22] PA History Q,[72] PYTPAQ,[26] Singh Q,[77,78] SQUASH,[32] Historical walking, running and jogging questionnaire,[30] NPAQ,[20] Health Insurance Plan of NY,[3] TOQ[31,89] London PA Q[88]). Unfortunately, for only 13 of these 23 questionnaires was both reliability and construct validity studied (Bharati,[45] EPIC original Q,[10] EPAQ2,[9] Harvard/College Alumnus Q,[3,51] Kaiser PA Survey,[56] the long version of the IPAQ,[14] Norman Q,[70] One-week recall Q,[71] PYTPAQ,[26] Singh Q,[77,78] SQUASH,[32] Health Insurance Plan of NY,[3] TOQ[31,89]).

Of the 23 questionnaires with sufficient content validity, the Kaiser PA Survey,[56] the Godin Q,[50] the NPAQ,[20] Bharati Q,[45] the LUS version of the IPAQ,[14] One-week recall Q,[71] and the Health Insurance Plan of NY[3] scored good for reliability at Level 1 or 2. Construct validity was sufficient according to our criteria only for the L7S version of the IPAQ in one study,[92] although validity for the Kaiser PA Survey[56] was 0.49, which is only just below the (arbitrarily chosen) cut-off point of 0.50.

In recent studies, the IPAQ seems to be used most often and it is by far the most widely validated questionnaire at present.[14,91–95,97,107] Reliability of the IPAQ was not shown consistently within or between studies, although the short version for the past 7 days (S7S) and the long version for a usual week (LUS) seemed to perform best. We therefore recommend additional reliability studies of the IPAQ. Validity of the IPAQ seems questionable. First, content validity of the short forms seems limited because it does not discriminate between different settings. The long form, which does discriminate between five settings therefore has a better content validity, but it was reported to be “too boring and repetitive” and too long for routine surveillance.[14] The construct validity of both the short and the long forms varied widely, but were mostly below our criteria. Of the self-administered IPAQ forms, only for the L7S was a correlation found with an accelerometer – of 0.52 found in Finland[14] and 0.55 in Sweden[92] – and for the S7S in the US in men only.[95] Discrimination of the IPAQ between groups of people with different activity levels as measured with DLW[94] was questionable, although differentiation between groups with different fitness levels was adequate.[91] Therefore, we feel that additional well designed studies on the measurement properties, with specific attention to responsiveness, of the IPAQ are required.

3.3 Recommendations for Further Research

For future studies, we recommend choosing from the abovementioned 23 questionnaires that we identified as having sufficient content validity, and validating those further for reliability, construct validity and especially responsiveness.

The results of this review indicate that one study on validity and reliability of a questionnaire is not enough. A number of other questionnaires were validated in more than one study, and without exception the results were conflicting: the questionnaires showed sufficient validity in one study and not in another. Also, in the large international study on validity and reliability of the IPAQ, huge differences were found between countries. This indicates that it is important for researchers to assess the measurement properties of a questionnaire in their own language and in their own target population. As the majority of the studies on measurement properties of PA questionnaires have been conducted in the US, it remains to be seen whether the results can be generalized to other countries. We therefore strongly recommend researchers to assess measurement properties of a questionnaire carefully in their own target group.

Although PA questionnaires are frequently used for the evaluation of the effects of intervention, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the responsiveness of these questionnaires. A prerequisite for detecting differences in PA after an intervention would be that the questionnaire is responsive to change. The two studies assessing responsiveness did not show positive results in that regard.

Finally, more attention should be paid to reporting on studies assessing measurement properties of PA questionnaires, since, for instance, it was often unclear what questionnaire was used and for what purpose the questionnaire was intended. The QAPAQ might be a useful tool when reporting on measurement properties.

4. Conclusions

Based on our review of the literature concerning measurement properties of questionnaires measuring PA, no conclusion can be drawn regarding the best questionnaire at the moment. Researchers should determine which questionnaire would fit their purposes best regarding the content of the questionnaire. Questionnaires with good content validity need to be validated in well designed studies and in different countries. Data on the responsiveness of PA questionnaires are urgently needed for the use of questionnaires in intervention studies.

References

Powell KE, Thompson PD, Caspersen CJ, et al. Physical activity and the incidence of coronary heart disease. Annu Rev Public Health 1987; 8: 253–87

Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctionsfor health-related research. Public Health Rep 1985; 100 (2): 126–31

Jacobs Jr DR, Ainsworth BE, Hartman TJ, et al. A simultaneous evaluation of 10 commonly used physical activityquestionnaires. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993; 25 (1): 81–91

Richardson MT, Ainsworth BE, Wu HC, et al. Ability of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC)/Baecke Questionnaire to assess leisure-time physical activity. Int JEpidemiol 1995; 24 (4): 685–93

Jacobs J, Hahn LP, Haskell WL, et al. Validity and reliability of short physical activity history: Cardia and theMinnesota Heart Health Program. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 1989; 9 (11): 448–59

Resnicow K, McCarty F, Blissett D, et al. Validity of a modified CHAMPS physical activity questionnaireamong African-Americans. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003; 35 (9): 1537–45

Altschuler A, Picchi T, Nelson M, et al. Physical activity questionnaire comprehension: lessons from cognitive interviews. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009; 41 (2): 336–43

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL, et al. Protocol of the COSMIN study: COnsensus-based Standards for the selectionof health Measurement INstruments. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006 Jan 24; 6: 2

Wareham NJ, Jakes RW, Rennie KL, et al. Validity and repeatability of the EPIC-Norfolk Physical Activity Questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol 2002; 31 (1): 168–74

Pols MA, Peeters PH, Ocke MC, et al. Relative validity and repeatability of a new questionnaire on physical activity. Prev Med 1997; 26 (1): 37–43

Chasan-Taber L, Erickson JB, McBride JW, et al. Reproducibility of a self-administered lifetime physical activityquestionnaire among female college alumnae. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 155 (3): 282–9

Kurtze N, Rangul V, Hustvedt BE, et al. Reliability and validity of self-reported physical activity in the Nord-Trondelag Health Study: HUNT 1. Scand J Public Health 2008; 36 (1): 52–61

Kurtze N, Rangul V, Hustvedt BE, et al. Reliability and validity of self-reported physical activity in the Nord-Trondelag Health Study (HUNT 2). Eur J Epidemiol 2007; 22 (6): 379–87

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability andvalidity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003; 35 (8): 1381–95

Iwai N, Hisamichi S, Hayakawa N, et al. Validity and reliability of single-item questions about physical activity. J Epidemiol 2001; 11 (5): 211–8

Walsh MC, Hunter GR, Sirikul B, et al. Comparison of self-reported with objectively assessed energy expenditurein black and white women before and after weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 79 (6): 1013–9

Roeykens J, Rogers R, Meeusen R, et al. Validity and reliability in a Flemish population of the WHO-MONICA Optional Study of Physical Activity Questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998; 30 (7): 1071–5

Miller DJ, Freedson PS, Kline GM. Comparison of activity levels using the Caltrac accelerometer and five questionnaires. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1994; 26 (3): 376–82

Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol 1994; 23 (5): 991–9

Giles-Corti B, Timperio A, Cutt H, et al. Development of a reliable measure of walking within and outside the local neighborhood: RESIDE’s Neighborhood Physical Activity Questionnaire. Prev Med 2006; 42 (6): 455–9

Maddison R, Ni MC, Jiang Y, et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) and New Zealand Physical Activity Questionnaire (NZPAQ): a doubly labelled water validation. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2007 Dec 3; 4: 62

Bernstein M, Sloutskis D, Kumanyika S, et al. Data-based approach for developing a physical activity frequencyquestionnaire. Am J Epidemiol 1998; 147 (2): 147–54

Copeland JL, Kowalski KC, Donen RM, et al. Convergent Validity of the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adults:the new member of the PAQ family. J Phys Act Health 2005; 2 (2): 216

Aadahl M, Jorgensen T. Validation of a new self-report instrument for measuring physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003; 35 (7): 1196–202

Aadahl M, Kjaer M, Kristensen JH, et al. Self-reported physical activity compared with maximal oxygen uptakein adults. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007; 14 (3): 422–8

Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, Neilson HK, et al. Reliability and validity of the Past Year Total Physical Activity Questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol 2006; 163 (10): 959–70

Ferrari P, Friedenreich C, Matthews CE. The role of measurement error in estimating levels of physical activity. Am J Epidemiol 2007; 166 (7): 832–40

Berthouze SE, Minaire PM, Chatard JC, et al. A new tool for evaluating energy expenditure: the “QAPSE” developmentand validation. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993; 25 (12): 1405–14

Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, van Poppel MNM, et al. Qualitative attributes and measurement properties of physicalactivity questionnaires: the QAPAQ checklist. Sports Med 2010; 40 (7): 525–37

Bowles HR, FitzGerald SJ, Morrow Jr JR, et al. Construct validity of self-reported historical physical activity. Am JEpidemiol 2004; 160 (3): 279–86

Ainsworth BE, Jacobs Jr DR, Leon AS, et al. Assessment of the accuracy of physical activity questionnaire occupationaldata. J Occup Med 1993; 35 (10): 1017–27

Wendel-Vos GC, Schuit AJ, Saris WH, et al. Reproducibility and relative validity of the short questionnaire toassess health-enhancing physical activity. J Clin Epidemiol 2003; 56 (12): 1163–9

Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health statusquestionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 2007; 60 (1): 34–42

Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003

de Vet HCW. Observer reliability and agreement. In: Armitage P, Colton T, editors. Encyclopedia of biostatistics. Boston (MA): John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1998: 3123–8

Deyo RA, Centor RM. Assessing the responsiveness of functional scales to clinical change: an analogy to diagnostictest performance. J Chronic Dis 1986; 39: 897–906

Brown WJ, Burton NW, Marshall AL, et al. Reliability and validity of a modified self-administered version of the Active Australia physical activity survey in a sample of midagewomen. Aust NZ J Public Health 2008; 32 (6): 535–41

Dishman RK, Steinhardt M. Reliability and concurrent validity for a 7-d re-call of physical activity in collegestudents. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1988; 20 (1): 14–25

Aires N, Selmer R, Thelle D. The validity of self-reported leisure time physical activity, and its relationship to serumcholesterol, blood pressure and body mass index: a populationbased study of 332,182 men and women aged 40-42 years. Eur J Epidemiol 2003; 18 (6): 479–85

Staten LK, Taren DL, Howell WH, et al. Validation of theArizona Activity Frequency Questionnaire using doublylabeled water. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001; 33 (11): 1959–67

Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiologicalstudies. Am J Clin Nutr 1982; 36 (5): 936–42

Albanes D, Conway JM, Taylor PR, et al. Validation and comparison of eight physical activity questionnaires. Epidemiology 1990; 1 (1): 65–71

Pols MA, Peeters PH, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, et al. Validity and repeatability of a modified Baecke questionnaire onphysical activity. Int J Epidemiol 1995; 24 (2): 381–8

Canon F, Levol B, Duforez F. Assessment of physical activity in daily life. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1995; 25 Suppl.1: S28–34

Bharathi AV, Sandhya N, Vaz M. The development & characteristics of a physical activity questionnaire forepidemiological studies in urban middle class Indians. Indian J Med Res 2000; 111: 95–102

Carter-Nolan PL, Adams-Campbell LL, Adams-Campbell LL, et al. Validation of physical activity instruments: Black Women’sHealth Study. Ethn Dis 2006; 16 (4): 943–7

Wareham NJ, Jakes RW, Rennie KL, et al. Validity and repeatability of a simple index derived from the shortphysical activity questionnaire used in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition(EPIC) study. Public Health Nutr 2003; 6 (4): 407–13

Matton L, Wijndaele K, Duvigneaud N, et al. Reliability and validity of the Flemish Physical Activity Computerized Questionnaire in adults. Res Q Exerc Sport 2007; 78 (4): 293–306

Gionet NJ, Godin G. Self-reported exercise behavior of employees: a validity study. J Occup Med 1989; 31 (12): 969–73

Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci 1985; 10 (3): 141–6

Ainsworth BE, Leon AS, Richardson MT, et al. Accuracy of the College Alumnus Physical Activity Questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol 1993; 46 (12): 1403–11

Strath SJ, Bassett Jr DR, Swartz AM. Comparison of the college alumnus questionnaire physical activity index withobjective monitoring. Ann Epidemiol 2004; 14 (6): 409–15

Siconolfi SF, Lasater TM, Snow RC, et al. Self-reported physical activity compared with maximal oxygen uptake. Am J Epidemiol 1985; 122 (1): 101–5

Graff-Iversen S, Anderssen SA, Holme IM, et al. An adapted version of the long International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-L): construct validity in alow-income, multiethnic population study from Oslo,Norway. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2007 April 20; 4: 13

Graff-Iversen S, Anderssen SA, Holme IM, et al. Two short questionnaires on leisure-time physical activity comparedwith serum lipids, anthropometric measurements andaerobic power in a suburban population from Oslo,Norway. Eur J Epidemiol 2008; 23 (3): 167–74

Ainsworth BE, Sternfeld B, Richardson MT, et al. Evaluation of the kaiser physical activity survey in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000; 32 (7): 1327–38

Salonen JT, Lakka T. Assessment of physical activity in population studies: validity and consistency of the methodsin the Kuopio ischemic heart disease risk factor study. Scand J Sports Sci 1987; 9 (3): 89–95

Hopkins WG, Wilson NC, Russell DG. Validation of the physical activity instrument for the Life in New Zealandnational survey. Am J Epidemiol 1991; 133 (1): 73–82

Ainsworth BE, Jacobs Jr DR, Leon AS. Validity and reliability of self-reported physical activity status: the Lipid Research Clinics questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993; 25 (1): 92–8

Lof M, Hannestad U, Forsum E. Assessing physical activity of women of childbearing age: ongoing work todevelop and evaluate simple methods. Food Nutr Bull 2002; 23 (3 Suppl.): 30–3

Parker DL, Leaf DA, McAfee SR. Validation of a new questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physicalactivity. Ann Sports Med 1988; 4 (2): 72–81

Kohl HW, Blair SN, Paffenbarger Jr RS, et al. A mail survey of physical activity habits as related to measuredphysical fitness. Am J Epidemiol 1988; 127 (6): 1228–39

Taylor HL, Jacobs Jr DR, Schucker B, et al. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis 1978; 31 (12): 741–55

Weller IM, Corey PN. A study of the reliability of the Canada Fitness Survey questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998; 30 (10): 1530–6

Blair SN, Dowda M, Pate RR, et al. Reliability of long-term recall of participation in physical activity by middle-agedmen and women. Am J Epidemiol 1991; 133 (3): 266–75

Wilbur J, Holm K, Dan A. A quantitative survey to measure energy expenditure in midlife women. J Nurs Meas 1993; 1 (1): 29–40

Conway JM, Irwin ML, Ainsworth BE. Estimating energy expenditure from the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity and Tecumseh Occupational Activity questionnaires:a doubly labeled water validation. J Clin Epidemiol 2002; 55 (4): 392–9

Mundal R, Erikssen J, Rodahl K. Assessment of physical activity by questionnaire and personal interview withparticular reference to fitness and coronary mortality. EurJ Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1987; 56 (3): 245–52

Chasan-Taber S, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire for male health professionals. Epidemiology 1996; 7 (1): 81–6

Norman A, Bellocco R, Bergstrom A, et al. Validity and reproducibility of self-reported total physical activity:differences by relative weight. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25 (5): 682–8

Timperio A, Salmon J, Crawford D. Validity and reliability of a physical activity recall instrument among overweightand non-overweight men and women. J Sci Med Sport 2003; 6 (4): 477–91

Sidney S, Jacobs Jr DR, Haskell WL, et al. Comparison of two methods of assessing physical activity in theCoronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults(CARDIA) Study. AmJ Epidemiol 1991; 133 (12): 1231–45

Lowther M, Mutrie N, Loughlan C, et al. Development of a Scottish physical activity questionnaire: a tool for usein physical activity interventions. Br J Sports Med 1999; 33 (4): 244–9

Marsden J, Jones RB. Validation of Web-based questionnaires regarding osteoporosis prevention in youngBritish women. Health Bull (Edinb) 2001; 59 (4): 254–62

Bulley C, Donaghy M, Payne A, et al. Validation and modification of the Scottish Physical Activity Questionnairefor use in a female student population. Int JHealth Promot Edu 2005; 43 (4): 117–24

Wilbur J, Miller A, Dan AJ, et al. Measuring physical activity in midlife women. Public Health Nurs 1989; 6 (3): 120–8

Singh PN, Tonstad S, Abbey DE, et al. Validity of selected physical activity questions in white Seventh-day Adventistsand non-Adventists. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996; 28 (8): 1026–37

Singh PN, Fraser GE, Knutsen SF, et al. Validity of a physical activity questionnaire among African-AmericanSeventh-day Adventists. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001; 33 (3): 468–75

Schechtman KB, Barzilai B, Rost K, et al. Measuring physical activity with a single question. Am J Public Health 1991; 81 (6): 771–3

Arroll B, Jackson R, Beaglehole R. Validation of a threemonth physical activity recall questionnaire with a sevendayfood intake and physical activity diary. Epidemiology 1991; 2 (4): 296–9

Suzuki I, Kawakami N, Shimizu H. Reliability and validity of a questionnaire for assessment of energy expenditureand physical activity in epidemiological studies. J Epidemiol 1998; 8 (3): 152–9

Lagerros YT, Mucci LA, Bellocco R, et al. Validity and reliability of self-reported total energy expenditure using anovel instrument. Eur J Epidemiol 2006; 21 (3): 227–36

Li S, Carlson E, Holm K. Validation of a single-item measure of usual physical activity. Percept Mot Skills 2000; 91 (2): 593–602

Tsubono Y, Tsuji I, Fujita K, et al. Validation of walking questionnaire for population-based prospective studiesin Japan: comparison with pedometer. J Epidemiol 2002; 12 (4): 305–9

Bassett Jr DR, Cureton AL, Ainsworth BE. Measurement of daily walking distance-questionnaire versus pedometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000; 32 (5): 1018–23

Dolan SH, Williams DP, Ainsworth BE, et al. Development and reproducibility of the bone loading historyquestionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006; 38 (6): 1121–31

Eagan MS, Lyle RM, George PM, et al. A new selfreported comprehensive historical activity questionnairefor young women. J Phys Act Health 2005; 2 (1): 35

Suleiman S, Nelson M. Validation in London of a physical activity questionnaire for use in a study of postmenopausalosteopaenia. J Epidemiol Community Health 1997; 51 (4): 365–72

Ainsworth BE, Richardson MT, Jacobs Jr DR, et al. Accuracy of recall of occupational physical activity byquestionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol 1999; 52 (3): 219–27

Rundle A, Hagins M, Orjuela M, et al. Traditional physical activity indexes derived from the Harvard Alumni Activity Survey have low construct validity in a lower income, urbanpopulation. Urban Health 2008; 84 (5): 722–32

Fogelholm M, Malmberg J, Suni J, et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: validity against fitness. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006; 38 (4): 753–60

Hagstromer M, Oja P, Sjostrom M. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrentand construct validity. Public Health Nutr 2006; 9 (6): 755–62

Dinger MK, Behrens TK, Han JL. Validity and reliability of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire incollege students. Am J Health Edu 2006; 37 (6): 337–43

Ishikawa-Takata K, Tabata I, Sasaki S, et al. Physical activity level in healthy free-living Japanese estimated bydoubly labelled water method and International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008 Jul; 62 (7): 885–91

Wolin KY, Heil DP, Askew S, et al. Validation of the international physical activity questionnaire-short amongblacks. J Phys Act Health 2008; 5 (5): 746–60

MacFarlane DJ, Lee CCY, Ho EYK, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of IPAQ (short, last 7days). J Sci Med Sport 2007; 10 (1): 45–51

Vandelanotte C, de Bourdeaudhuij I, Philippaerts R, et al. Reliability and validity of a computerized and Dutchversion of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire(IPAQ). J Phys Act Health 2005; 2 (1): 63

Rosenberg DE, Bull FC, Marshall AL, et al. Assessment of sedentary behavior with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. J Phys Act Health 2008; 5 Suppl.1: S30–44

Slattery ML, Jacobs Jr DR. The inter-relationships of physical activity, physical fitness, and body measurements. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1987; 19 (6): 564–9

Leicht A. Validation of a one-day self-report questionnaire for physical activity assessment in healthy adults. Eur JSport Sci 2008; 8 (6): 389–97

Kwak L, Kremers SPJ, van Baak MA, et al. Measuring physical activity in field studies: comparison of a questionnaire,24-hour recall and an accelerometer. Eur JSport Sciences 2007; 7 (4): 193–201

Chasan-Taber L, Erickson JB, Nasca PC, et al. Validity and reproducibility of a physical activity questionnaire inwomen. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002; 34 (6): 987–92

Hopkins WG, Wilson NC, Worsley FA, et al. Reliability of the core questionnaire in the life in New Zealand Survey. NZ J Health Phys Edu Rec 1991; 24 (3): 21–2

Lof M, Hannestad U, Forsum E. Comparison of commonly used procedures, including the doubly-labelledwater technique, in the estimation of total energy expenditureof women with special reference to the significanceof body fatness. Br J Nutr 2003; 90 (5): 961–8

Conway JM, Seale JL, Jacobs Jr DR, et al. Comparison of energy expenditure estimates from doubly labeled water, aphysical activity questionnaire, and physical activity records. Am J Clin Nutr 2002; 75 (3): 519–25

Terwee CB, Dekker FW, Wiersinga WM, et al. On assessing responsiveness of health-related quality of life instruments: guidelines for instrument evaluation. Qual Life Res 2003; 12 (4): 349–62

Kurtze N, Rangul V, Hustvedt BE. Reliability and validity of the international physical activity questionnairein the Nord-Trondelag health study (HUNT)population of men. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008 Oct 9

Acknowledgements

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this review. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Poppel, M.N.M., Chinapaw, M.J.M., Mokkink, L.B. et al. Physical Activity Questionnaires for Adults. Sports Med 40, 565–600 (2010). https://doi.org/10.2165/11531930-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11531930-000000000-00000