Abstract

Objective

To assess the efficacy of patient-centered label (PCL) instructions on the knowledge and comprehension of prescription drug use compared to standard instructions.

Methods

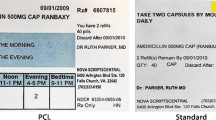

A total of 94 participants recruited from an outpatient clinic in Ireland were each randomly assigned to receive: (1) standard prescription instructions written as times per day (usual care), (2) PCL instructions that specify explicit timing with standard intervals (morning, noon, evening, bedtime) or with mealtime anchors (both PCL), or (3) PCL instructions with a graphic aid to visually depict dose and timing of the medication (PCL + Graphic). The outcome was correct interpretation of the instructions.

Results

PCL instructions were more likely to be correctly interpreted than the standard instructions [adjusted relative risk (RR) 1.08, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.98–1.18]. The inclusion of the graphic aid (PCL + Graphic) decreased the rates of correct interpretation compared to PCL instructions alone (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.91–1.05). There was a significant interaction between instruction type and health literacy (p = 0.01). Those with limited health literacy were more likely to correctly interpret the PCL labels (91%) than the standard labels (66%), and those with adequate health literacy performed equally well.

Conclusion

The PCL approach may improve patients’ understanding and use of their medication regimen.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF et al (2006) Low literacy impairs comprehension of prescription drug warning labels. J Gen Intern Med 21:847–851

Wolf MS, Davis TC, Bass PF et al (2006) Misunderstanding prescription drug warning labels among patients with low literacy. Am J Health System Pharm 63:1048–1055

Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF et al (2006) Literacy and misunderstanding of prescription drug labels. Ann Intern Med 145:887–894

Wolf MS, Davis TC, Shrank W et al (2007) To err is human: patient misinterpretations of prescription drug dosage instructions. Pat Educ Counsel 67:293–300

Shrank WH, Agnew-Blais J, Choudhry N et al (2007) The variability and poor quality of medication container labels: a prescription for confusion. Arch Intern Med 167:1760–1765

Committee on Identifying and Preventing Medication Errors, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine of the National Academies (2006) In: Aspden P, Wolcott J, Bootman JL, Cronenwett LR (eds) Quality chasm series: preventing medication errors. National Academies Press, Washington D.C.

Roundtable on Health Literacy, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, Institute of Medicine (2008). In: Hernandez LM (ed) Standardizing medication labels: confusing patients less. Workshop summary. National Academies Press, Washington D.C.

Bailey SC, Persell S, Jacobson KA et al (2009) Comparison of hand-written and electronically-generated prescription drug instructions. Ann Pharmacother 43:151

Wolf MS, Shrank WH, Choudry N et al (2009) Variability of pharmacy interpretations of physician prescriptions. Med Care 47:370–373

Medicinal Products (Prescription and Control of Supply) Regulations 2003 to 2009. Irish Statute Book, Statutory Office, Dublin

Wolf MS, Davis TC, Curtis LM et al (2011) Effect of standardized, patient-centered label instructions to improve comprehension of prescription drug use. Med Care 49:96–100

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975) Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12:189–198

Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH et al (1993) Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med 25:256–260

McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X et al (2003) Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 157:940–943

Zou G (2004) A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 159:702–706

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the participants of the study for their time and the staff of the hospital for facilitating the study.

Statement of conflict of interest

None.

Funding

No external funding was received for the conduct of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sahm, L.J., Wolf, M.S., Curtis, L.M. et al. What’s in a label? An exploratory study of patient-centered drug instructions. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 68, 777–782 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-011-1169-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-011-1169-2